In Aesop’s Fables, a set of tales told to children to imbue them with socially correct morals, exists the story of “The North Wind and The Sun.” The iconic fable describes how the anthropomorphic entities of the Wind and the Sun argued between themselves on the best method in getting someone to remove their coat. After the Wind, through blusterous methods, fails where the gentle pervasive heat from the Sun succeeds, a simple story is told on how the outcome you desire can be achieved with a gentle touch rather than through brute force. Writer-Director Aaron Schimberg has seemingly never taken that moral on board as A Different Man, a fascinating metatextual black satire, tells a relatively simple moral about accepting oneself and on the societal fallacy of beauty in your appearance through a brash, and occasionally arrogant, method of execution.

Sebastian Stan’s Edward: A Man Defined by Stigma

Edward (Sebastian Stan, in a career-best performance), a struggling and introverted actor in New York, has a severe facial condition that he believes is preventing him from getting jobs. His ‘disfigurement’ garners attention in the form of courteous nods that fail to hide curiosity and the sly glances and hushed whispers that occur on the train and while walking down the street, which only contribute to the stigma Edward feels around his condition.

This is exacerbated by the arrival of flirty neighbor and playwright Ingrid (Renate Rensieve), who quickly becomes fond of Edward. The two begin a friendship, one where Edward gifts her an expensive red typewriter he never gets to use, but it is consistently on the precipice of being sexual. It seems Ingrid wants to take things further, but, for reasons we can only infer, she doesn’t allow it. It soon becomes apparent to Edward that he will never get Ingrid, as a sexual prospect at the least, due to his disfigurement, and he seeks treatment for his condition.

While in the beginning stages of the medical trial that may or may not ‘fix’ his condition, he is given a reconstruction of his own face in the form of a mask. During a fervid and sweaty metamorphosis straight from the An American Werewolf in London playbook, Edward sheds (Stan, illuminated by the crackle of thunder and lightning literally tearing off the prosthetic make-up) his disfigurement, becoming conventionally attractive and what he thinks will make him desirable to hire, but more importantly to be loved.

Sebastian Stan’s Dual Performance

This sets the stage – pun intended – for Edward, the actor, to take on a new name, allowing Edward, whom people knew, to die in the eyes of those close to him. Edward, from now on referred to as Guy, spreads his newfound socially acceptable wings and vacates his tidy but compact lodgings. After a time jump, Guy now works as a real estate seller, a job that normally desires charismatic, conventionally attractive people to tell you what you want. This time jump marks the first time that the film becomes indebted to Synecdoche, New York – a film with slight surrealism and chronological shenanigans – but also as both construct their narratives around stage productions.

That Guy vacates the building so quickly and without attempting to explain to anyone, especially Ingrid, felt like a bum note within the motivation and characterization of Edward, in which an attempt to use his newfound handsomeness to woo Ingrid was a natural development as he instead creates a new life for himself. That is until Guy walks down the street and spots an off-Broadway production looking for its star. They’re looking for someone to play a lonely, introverted man. A disfigured man with a red typewriter. A man called Edward, in a play called Edward. One written by Ingrid.

This is where Schimberg starts to bring the playful meta-threads the script has been weaving together on identity, anxiety, and the literal and figurative masks we wear to protect ourselves, and if such protection is often the right course of action. The film begins to discuss larger concepts around Hollywood casting procedures and that of method acting as Guy tries out for the part of Edward, donning the mask given to him prior to the treatment, transforming him back – in less refined fashion than when it was 2 hours of make-up each morning for actor Sebastian Stan – into Edward. Ingrid, who doesn’t seem to question how the mask that Guy has emerged with is an expected replica of Edward’s face prior to his apparent death, casts Guy in the lead role.

Schimberg then funnels this into a conversation to be had around representation. Ingrid had intended to cast someone with facial disorders but was astounded that Guy could perfectly capture Edward’s awkward, hunched-back mannerisms along with Edward’s inner angst. The film is laced with dramatic irony as Guy is, of course, Edward. That notion, plus the appearance of the suave, confident Oswald (Adam Pearson), brings together all of Schimberg’s thematic purpose: Guy is Theseus’s Ship. He is still the same self-defeating, emotionally stagnant pessimist. The same broom with a different handle.

Adam Pearson’s Oswald – The Highlight of A Different Man

The play’s the thing, though, and the theatrical adaptation of Edward’s life before his “death” takes multiple comedic turns that help steer Schimberg’s themes of exploitation and, ultimately, the optics around casting. Oswald (Pearson is himself an actor with a real facial condition called neurofibromatosis, widely known for his appearance in Under The Skin) challenges Guy on the authenticity of portraying someone with a facial condition when Guy doesn’t have one, and unbeknownst to them, never has. It’s layered and playful enough within these layers that it miraculously doesn’t collapse in on itself like the crumbling mental health of someone realizing their life is miserable because they made it so.

Oswald, through Adam Pearson’s magnetic performance in his supporting role, is the highlight. The kind of performance that provides enough oxygen for the flame that will light up a room to ignite. This is the point, after all. Oswald is a man who has everything Edward wanted and Guy could never have: charisma. Stan is excellent in his dual role. He pays Edward’s timidity perfectly, which feeds into how amateurish his acting is – what the film suggests is the real reason he doesn’t get acting gigs, while Guy’s bravado is all bluster, and his confidence as false as the mask he wears on stage. Stan manages to deftly capture each character in their own minute ways, in their similarities, their differences, and the eccentricities that both characters have, which made him so unwelcoming to people in the first place.

There are not many films quite like A Different Man. It is something original and unique in execution and functions as a critique of itself. But the knotty screenplay, which flits between being razor sharp and acting as a blunt tool to dictate its point, is often too smarmy. Schimberg cockily seems to think he’s writing profound material, but the script steps across metatextual boundaries in a way that eventually becomes obnoxious by its third act, one which flirts with even bigger concepts around ableism but has nothing to say about except posit its existence.

Echoes of Charlie Kaufman and Cynical Moral Exploration in A Different Man

Yet, strangely, the film and this big swing of a time-hopping third act still works. The meta satire of it all might wear thin, but Stan and Pearson, alongside Renseive, are dynamite on-screen presences, and the script crackles when it’s not purporting to be intelligent. It has the surreal energy of a Charlie Kaufman picture – that is to say, Synecdoche, New York specifically – and is absorbing and pleasing in its eccentricities. But ultimately, for a film that challenges societal ideas of beauty and champions our inner selves over aesthetics, doing this through cynically bleak methods feels counter-intuitive to the moral. The message may go through, but one believes audiences will firmly keep their metaphoric coats on at Schimberg’s turbulent bluster.

A Different Man will screen at the New Directors/New Films Festival in New York City in early April 2024.

You might also like…

‘Small Things Like These’ Review: Cillian Murphy in a Conversation Starter (Berlinale)

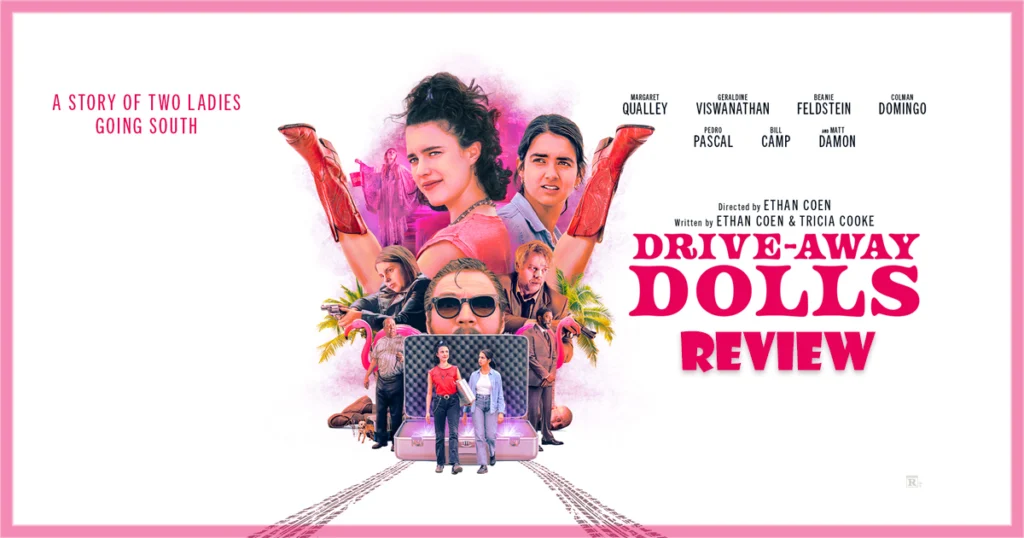

‘Drive-Away Dolls’ Movie Review: A Lightweight Labor of Love

SXSW ‘The Fall Guy’ Movie Review – Ryan Gosling and Emily Blunt Anchor a Fantastic Action Film