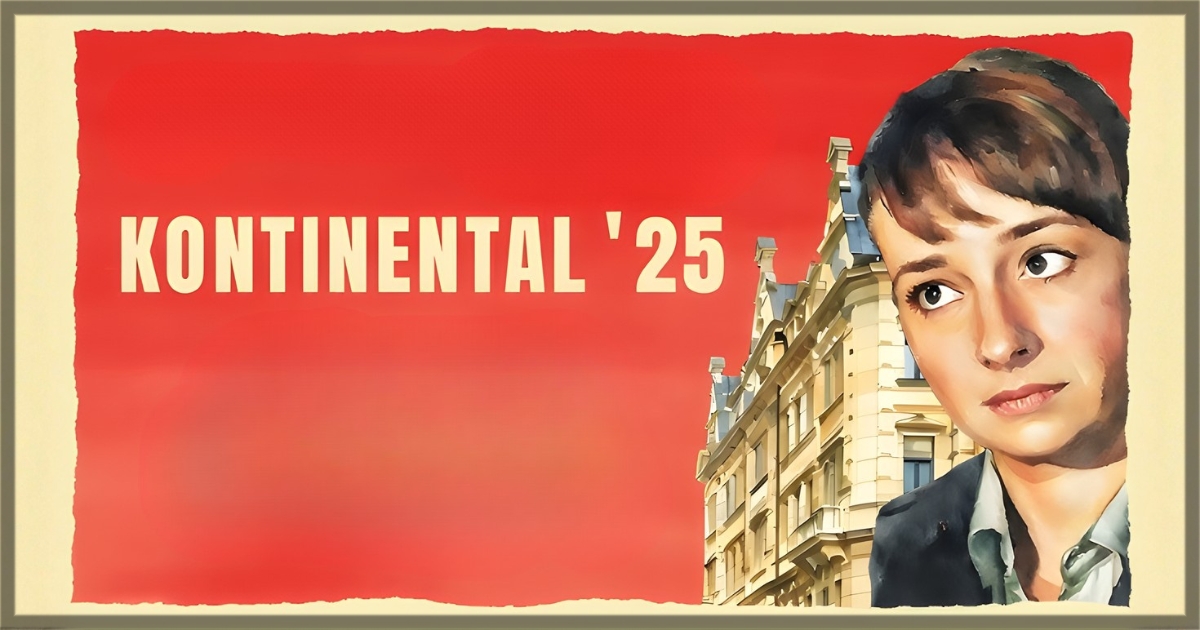

The Romanian director Radu Jude is one of the most prolific filmmakers of our time. A member of the Romanian New Wave, a group of new voices in the mid-2000s, which generated great works from Cristian Mungiu, Cristi Puiu, Corneliu Porumboiu, and Alexander Nanau. Since 2020, Jude has released 11 films, consisting of both short and feature-length productions. The director presented Uppercase Print, The Exit of the Trains, Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World, Eight Postcards from Utopia, Sleep #2, Kontinental ’25, and Dracula. Hence, these works premiered at the cinema’s principal events, such as Berlinale, where he won the Golden Bear in 2021 with Bad Luck. This year, he returned to the festival where he won one of the three central honors in the European festival circuit; now, he presents Kontinental ’25.

The first of the two films released by the Romanian director in 2025, Kontinental, is Jude’s take on Roberto Rossellini’s 1951 film Europe ’51. Shot on an iPhone in just 10 days of production, the film was made during the filming of the director’s second film of the year, Dracula. In a sense, the vanguardist borrows the independent spirit of the Italian film movement, shooting on location in the streets and wandering through the city’s constructions as sets. Yet, Jude continues the exploration of a theme that is present throughout his whole career: a disjointed Romania post-communism and joining the European Union. The director questions the growing inequalities between the social classes, benefiting from the capitalist system, and using the state machinery to protect their rights to profit.

In the film, we follow a homeless man (Gabriel Spahiu), a former athlete who lost his home and family due to his alcoholism and injuries. Therefore, he wanders around town, begging for money, and sleeps at night in a basement that belonged to another former athlete. Unfortunately, the past owner sold the building to a construction corporation, and the public department needs to evict the man from the basement. Orsolya (Eszter Tompa) is responsible for the eviction, who deploys the state’s forces to help with the action. However, when they enter the building, they encounter the man’s body, hanged on a radiator. Consequently, Orsolya suffers from the immense remorse of that event, grieving and mourning the suffering caused by her employment of a private company’s interests through the public structure.

Furthermore, the director’s realistic, simplistic approach elicits a direct reaction from the lead character. Orsolya suffers for a death she caused. If she had not evicted that individual, he would probably still be alive. Thus, the film is the ballad of a melancholic woman, who searches for comfort wandering through the city, in the same places the dead man used to. In the first moment, Orsolya is a miserable human who withdraws from her vacation in Greece with her family because of the heavy pain of that event. Morally, she feels guilty. Emotionally, she is a mess, someone who lost track of her productive routine and emotional control. She searches for words of consolation in her orthodox priest friend, who punctuates the absurdity of that situation, which does not imprint enough culpability in her character. Still, she searches for meaning and redemption in the streets that combine the new heights of a capitalist business model and the architecture of a bygone communist regime.

On a grander scale, Kontinental ’25 converses with different moments in cinema’s history. Firstly, the homage to the neo-realist movement, a post-war and reconstruction-of-Europe moment, where realism echoed the melancholy and sorrows of guilt, particularly in the context of post-Mussolini Italy. In a subsequent interpretation, Jude positions himself similarly to his Romanian peers, making films after the downfall of the Soviet Union, as a result of the failure of Communism as the ideal political and economic system, and studying the 21st-century neoliberal policies. The director searches for the comicness in the study of the intentional poverty caused by the ongoing economic regime, as he films it in the final shot of Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World. The Romanians are poorer and unassisted by the public service, while departments such as Orsolya’s utilize its infrastructure to guarantee the profitability of corporations. Jude mocks the results of left-wing policies in Romania over the last decade and explores corporate success, while citizens suffer from a lack of housing and dignified living.

Radu Jude is the filmmaker of our times. The one who questions the status quo and points fingers at the liberalism in his country, profiting while the masses lose benefits and conditions of living. In Kontinental ’25, he interrogates the public services as organizations within the bourgeoisie class, the ones who own the means of production. Still, the corporate greed established itself so profoundly that it shifts accountability to individuals, who are not responsible for its consequences, yet shield a post-capitalist system that smashes them.

Kontinental ’25 has recently played at a number of international film festivals.

Learn more about the film at the IMDB site for the title.