Miguel Gomes won the Best Director prize at this year’s Cannes Film Festival for Grand Tour, which he co-wrote with Telmo Churro, Maureen Fazendeiro, and Mariana Ricardo, because it is an impossible film. It’s an epic pan-Asian journey best described as a mash-up of Wisconsin Death Trip and Apocalypse Now, in which the visuals and voiceover are juxtaposed to show the world as it is as well as the world as it was. To describe it makes it sound unbelievable, which is frankly is, and the fact the movie is an undiluted triumph means Mr. Gomes deserves every prize the film industry can dream up.

The story of Grand Tour

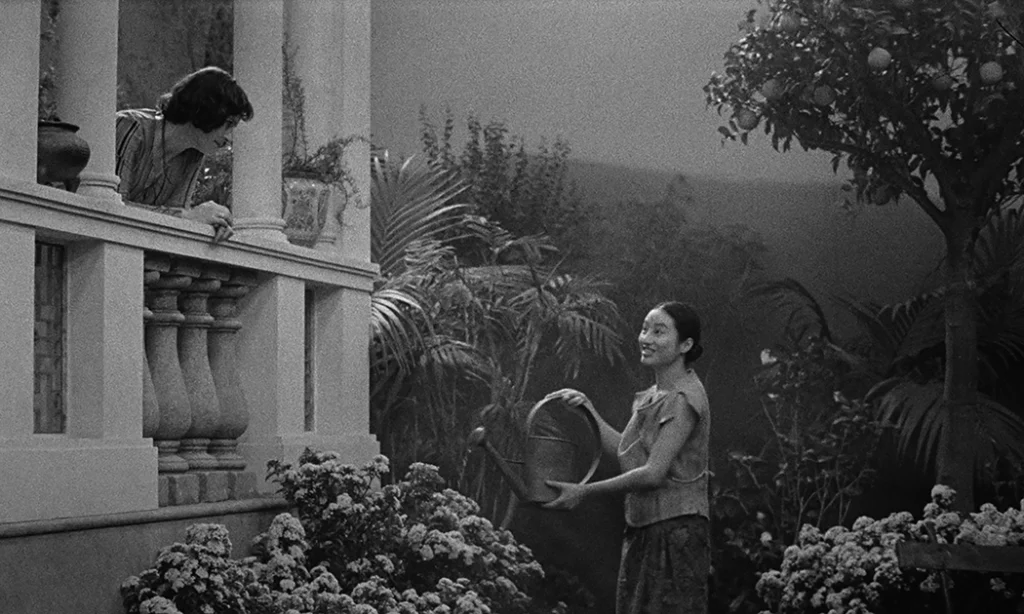

The basic plotline is this: it’s 1918, and Englishman Edward (Gonçalo Waddington) works in Rangoon. His cheerful fiancée Molly (Crista Alfaiate) is finally coming out from London after a separation of some years. But instead of meeting her on the dock as planned, Edward runs away, beginning a long, awkward, and aimless journey over land and sea through Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand, Japan, the Philippines, and China.

Molly is not surprised at all that Edward turned heel and pursues him, keeping tabs on his whereabouts through the gossip of the expat community and eventually with the assistance of a sweet woman named Ngoc (Lang Khê Tran). Molly’s firm yet delighted insistence that Edward remains her man is a sharp contrast to Edward’s equally firm insistence that he must keep running, even as he is not quite sure why. When anybody asks, he says that he loves her. And yet he keeps going.

Edward and Molly’s scenes are filmed in black and white and obviously filmed in a studio, not that this takes away from the set pieces, such as a train derailment in the jungle or a journey to a hillside monastery on the back of a mule. But the largest part of their story is told in voiceover, by a narrator from every country they pass through speaking the local language, as footage of what the places Edward and Molly saw look like now dazzle the screen.

The opening shots are of a Ferris wheel in Rangoon, one that’s manually spun by daredevil operators and climbed all over by laughing children without a moment’s regard for their physical safety. Shots of a man repairing some electric wires by sitting on them and other equally vivid documentary-style street shots provide a sense of danger that Molly and Edward’s olden-times journey somehow lacks. It shouldn’t, of course, not least in the days before penicillin and calling 911, but the distancing of black and white film can sometimes do that to you.

The contrast has the curious effect of allowing the story to sweep over you as you consider the clash between the tale and the images, and that consideration means Grand Tour becomes much more than its images or its plot. Wisconsin Death Trip (1999), about a series of strange events in a small Wisconsin town in the 1890s, used modern-day footage to demonstrate that our ideas of the past, such as the case of the cocaine-addicted window-smasher, can be stereotyped and unfair.

The Strange Allure of Grand Tour

Of course, so can the views of white expats in Asia, then and now, but Gomes worked with three cinematographers, Rui Poças, Gui Liang, and Sayombhu Mukdeeprom (who recently did such good work in Challengers), to minimize this bias. Mr. Waddington’s haunted face keeps Edward’s odd compulsion away from everything he’s ever known fresh and strangely understandable, while Ms. Alfaiate has the tougher job of ensuring her character finds her entire exhausting ordeal hilarious. But as in Apocalypse Now, the journey keeps going; only the horror that is found in a bamboo grove in rural China is of an entirely unexpected kind. Grand Tour is one of those compulsively strange movies that anyone interested in world cinema simply must see, and it’s so good it’s going to have a remarkable impact on how future stories are told.

Grand Tour recently screened at the Cannes Film Festival.

Learn more about the movie at the Cannes website for the title.