Ridley Scott’s 1979 masterpiece Alien was a tremendous achievement; A low-fi monolith of science-fiction horror that changed the landscape of film as we know it. From Ridley Scott’s lean and elegant direction to HR Giger’s phallic and genitalia-inspired character and set design, one which now feels fused into the very fabric of the franchise, the film is now a zenith of pop culture, an iconic classic that you’d be hard pushed to find a negative word about. It has even inspired endlessly interesting scholarly articles about the monstrous feminine of the Alien character, on how the film acts as a horror on the concept of male rape and even on the megalomaniacal company that financed the space mission was happy to kill the means of production in favour of profits.

The franchise has been molded, abused and transformed since Scott’s magnum opus. Populist darling Aliens was the first sequel, helmed by James Cameron before infamously studio-meddled Alien 3 (cubed) and a myriad of subpar installments, including a trilogy of films that combined two iconic 1980s monsters: the Xenomorph and Predator. But after a stint of cryo-sleep, Ridley Scott returned to the franchise he birthed with the idea of a new trilogy. This was 2012’s Prometheus and Alien: Covenant, prequels to his original work, with fresh ideas on how the Xenomorph came to be as an analogy for creationism.

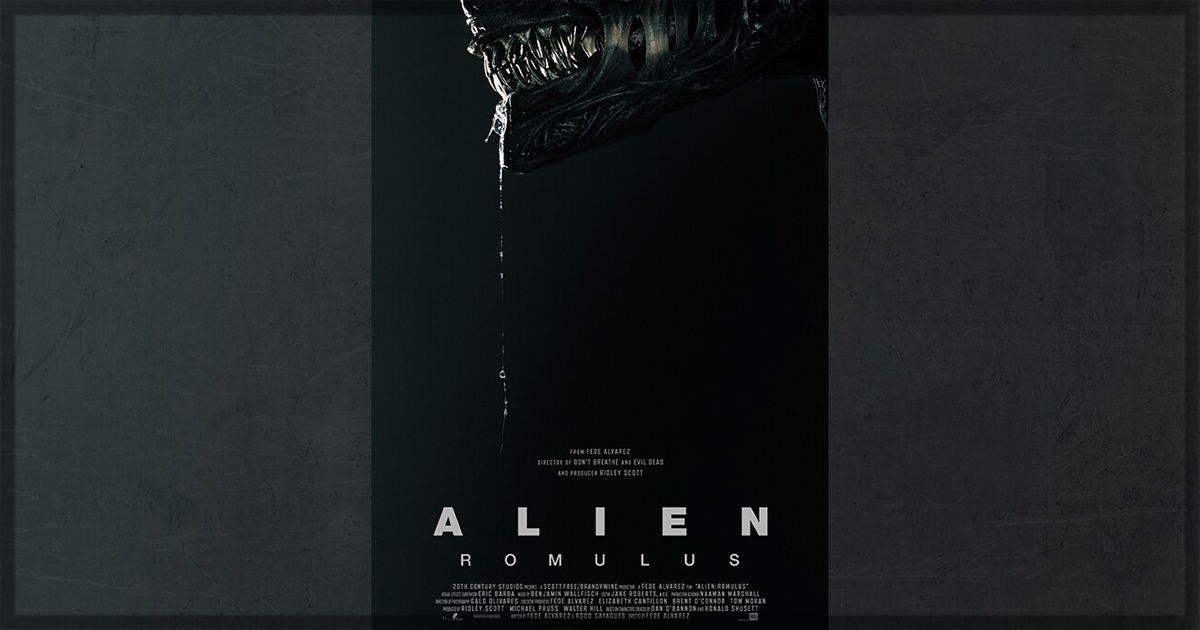

Unfortunately, these were not received well enough for 20th Century Fox (now Disney) to greenlight another Scott-directed production. But like good little IP, it is soon trotted out again for Alien: Romulus. This installment is directed by Fede Álvarez, the director behind acclaimed horror flicks Evil Dead (2013) and Don’t Breathe, who has spoken endlessly of his love for Alien and Aliens over the course of Romulus’ production. Sadly, it appears that Álvarez is more a fan of Aliens, as he takes the moody aesthetic of Alien and a chunk of the greatest memes of the franchise and transposes it to Romulus, a film that is more than happy to parade around in the skin of the franchise, Álvarez performing an Alien taxidermy.

In the most fitting visual metaphor for the film that you could ask for, Alien: Romulus opens with the franchise’s capitalist overlords, Weyland-Utani sending a ship to collect the petrified remains of the Xenomorph from the Nostromo, the ship from Alien. It fumbles through the ship’s carcass, retrieving what is dubbed the “most perfect organism” from Alien, which didn’t die after being expunged during the original film’s thrilling climax. Cut to our protagonist, Rain Carradine (Cailee Spaeny), an orphan who is working on a mining planet that receives zero hours of sunlight each day with her damaged, synthetic brother Andy (the films standout performer David Jonsson). She has earned enough credits to finally leave the workforce and travel to a distant planet, one fully terraformed whose sun shines bright across Rain’s face in her dreams.

However, capitalism rears its ugly head and doubles the required credits, forcing her to find a new method of escaping her proletariat upbringing. Luckily, and conveniently, her friends have just spotted an abandoned Weyland-Utani ship that might be able to get them to this paradise, but they need a synthetic, the franchise’s humanoid robot assistants, to interact with mu.th.ur, the ship’s mainframe. The ship docks with the abandoned ship, the one we see in the opening sequence. This is a completely tension-less scene as we have seen that the Xenomorph exists on this ship, so when everything begins going wrong, as the crab-like face-huggers thaw from stasis and begin attacking our protagonists, it just feels like an inevitability. Álvarez then chooses to frighten with some occasionally effective jumpscares, rather than an impending sense of dread.

Which is where I believe Álvarez doesn’t seem to like Alien in the same way that someone like myself does. Romulus has a set design not dissimilar to that of the Nostromo and follows a structure that is not dissimilar to Alien but it is castrated, as most of the psychosexual tension of the franchise is skirted past. It has the rugged techno junk aesthetic of Alien combined with the bluster of Aliens, but is a complete castration of what made Alien such a fierce work of art. It is a film that is all bark and no bite. When Xenomorphs start appearing en masse and are promptly shot down with headshots (with auto-aim, one of the many visual signifiers that make the picture feel like a video game), the film becomes numbing, the death of each Xenomorph becoming a more pleasing prospect than continuing with this grueling affair.

But continue you do and for some meagre rewards. The third act has grubby fingerprints of studio meddling – par for the course when it comes to the franchise – but at least the final twenty minutes of this attempts to break away from the very overly safe ninety minutes that precede it. The franchise’s idea of the Xenomorph undergoes a metamorphosis, working to continue and expand on the more psychosexual ideas of motherhood and nurturing that permeate the franchise. But these ideas are presented fragmentally, like the film (or perhaps Disney) is scared of these more inflammatory aspects.

It’s quite apparent that there is something really fascinating underneath this mess, one that scholars and the likes will unravel in time – lactation is all that can be said without spoilers – but elements of the picture, like physical sets and practical effects that should elicit excitement don’t seem to. Real physical sets are refreshing to see in a Disney production, but the practical effects – like an animatronic Xenomorph – are shrouded, both in literal darkness and in the edit. There is a hesitancy to the entire picture.

Not the least within some egregious call-backs to the franchise and what appears to be the use of deepfake technology (which reminded one of Henry Cavill’s infamous Justice League mustache) to resurrect a past face from the franchise, like the powers that be enforced guidelines that previous lines from the franchise must be repeated and characters must be referenced and a certain narrative structure must be followed.

This is blockbuster horror filmmaking from Fede Álvarez, who has real skill and a keen eye, but they seem to have handcuffs on, squandering its potential. An installment all too aware of its cultural reach, Alien: Romulus acts as an exhumation of the franchise, like the film has been buried on the ancient burial ground of Alien, its harpooned skeleton reaching out begging for death.

Alien: Romulus will be in theaters on August 16, 2024.

Learn more about the film, including how to get tickets, at the official website.