The Vietnamese director Trương Minh Quý was one of the highlights of the 2024 Cannes Film Festival with his film Viet and Nam. The film had an extensive festival season, including a main slate slot in the New York Film Festival and a Wavelength selection in the Toronto International Film Festival. One year later, the director joined forces with French director Nicolas Graux (Century of Smoke), with whom he had previously collaborated on the 2023 short film Porcupine in Tóc, giấy và nước (Hair, Water, Paper…). In their new effort, the duo study a woman who was born in a cave in Vietnam and how she relates to the nature around her, her first stay in Saigon, and her legacy. Hence, the new collaboration places Minh Quý again amidst the prestigious film events conversation, his latest work premiered at the Locarno Film Festival and won the second most acclaimed section of the festival, the Cineaste del Presenti competition.

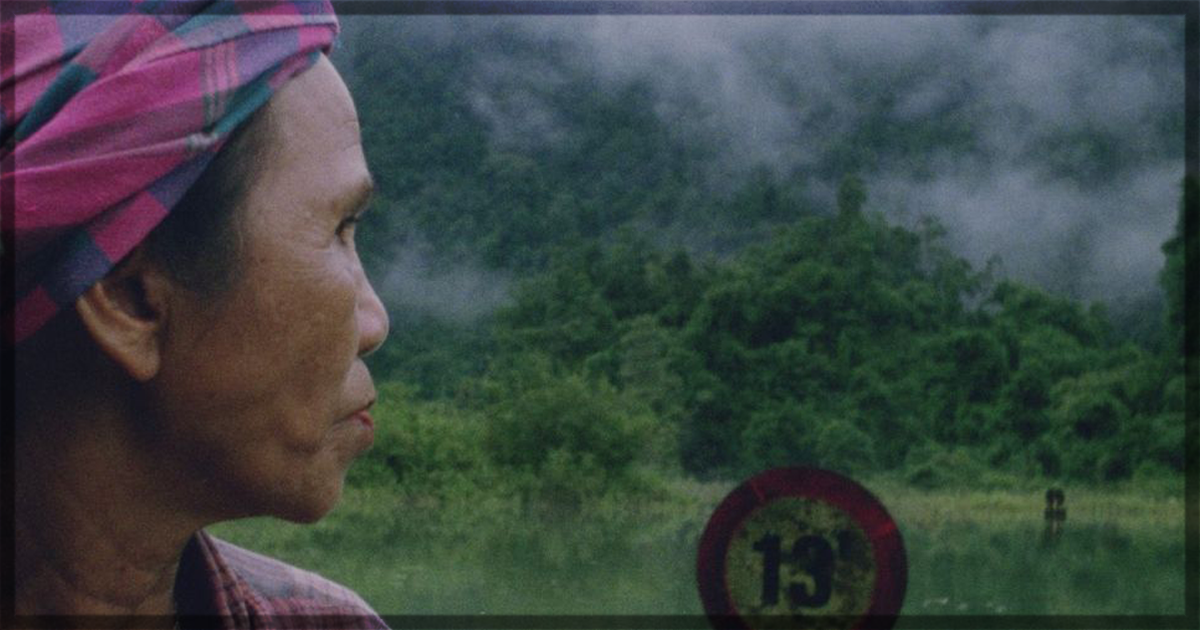

Firstly, the directing duo aims to create a sensorial documentation of Miss Cao Thị Hậu’s reality. She came from the cave, lives in the middle of the woods, and her life depends on extracting the natural goods to survive. In this sense, the directors decide to use the film material, the Super 16mm, to imprint a particular texture that poetically represents the mirroring of the forest. Furthermore, the 16mm responds well to the lack of lighting inside the cave in the introductory sequence, where the directors balance the light reflecting into the cave’s cavities in the film material, followed by a narration of the woman, and flashcards with sentences in Vietnamese. Since the first minute, the images tie the physical space to Hậu’s personality, creating an interconnection between who she is and the ambient around her. Thematically, the film presents how Hậu represents a generational clash; she raised her grandchildren and taught them Ruc, a language from a small ethnic group living within the country’s inner sides. The woman symbolizes an older generation of people who live in the villages, in contrast to the ongoing expansion of Saigon.

Therefore, the film is more interested in focusing on the physical and natural aspects of life rather than just a plain documentary on her biography. Consequently, we understand her persona through her actions. In the first scene of Hậu in the country’s capital, she fishes in a river in the margin of a large avenue, where thousands of vehicles commute to a final point. Her stay in the metropolis is to accompany her granddaughter, who has just given birth to a baby. Thus, the act of her caring for her great-grandchild highlights the differences between her manner of parenting and her granddaughter, who is a mother in a completely different context. Miss Hậu mixes herbs from the jungle to bathe the baby, using traditional popular medicine to care for a new life. There is a particular rejection of modernity, stressing a constant recurrence to tradition and the historical. Even the choice to film the documentary on film refers to this rescue of the antique labor form, dialoguing with Minh Quý’s Cannes film, also shot on film.

Still, the shift from the grandma’s perspective to her grandchildren diminishes the impact. The film analyzes the new generation of the Cao family, those who are learning from their grandmother’s example to construct a new age for that family, in a different time context. Yet, it is a loose documentation of the children’s experiences, which, for several reasons, including their short lives on Earth, is not as fascinating as the martyrdom of this family. Graux and Minh Quý are more interested in the documenting the costumes and that lifestyle which is disappearing with the country’s industrialization and modernization. As she mentioned, trivial elements such as her hair length would be fundamental to sell it to buyers and buy fish sauce, essential to the cooking of her household. It contrasts with a different context for her prole, who has varied opportunities, and the development of the productions means to earn money and raise their families. In the end, it is a sensory experience depending on Hậu’s central figure to tell the story of a vanishing language, land, and societal landscape in Vietnam.

Finally, Tóc, giấy và nước (Hair, Water, Paper…) uses the film to portray the differences in generations, society, and languages. Thus, it depends on Cao Thị Hậu’s story to engage the audience in a poetic experience. Still, it is a promising post-Cannes success career for Trương Minh Quý, and his cinema, which relies on Vietnamese culture and film material as a central element of the filmic experience to evoke emotion in people.

Tóc, giấy và nước (Hair, Water, Paper…) recently played at the Locarno Film Festival.

Learn more about the title at the Locarno site for the film.