Zeitgeisty trends combine in Peacock: how it mocks the vapid wealthy with lives so comfortable they must manufacture problems for themselves is clearly inspired by the work of Ruben Östlund. The problem is that social satire works best with a strong opinion about the behaviour being mocked. Are you teasing social media influencers lovingly, or are you sneering out of anger or class rage? For a movie about authenticity to feel like such a rip-off is quite the disappointment. And yet, there’s a nugget of truth inside Peacock which didn’t quite grow into a pearl, but is fascinating to examine all the same.

It takes a little while to be clear on what Matthias (Albrecht Schuch) does for a living, but eventually we realise he and his best friend David (Anton Noori) own a rent-a-friend business. If your son is too busy at his job overseas to attend your garden party, Matthias will come in his place and schmooze all your friends from your club. Your dad unavailable to impress all the other kids at school? Matthias will don a pilot’s uniform and an expression of pride for show-and-tell. You are an older lady (Maria Hofstätter) who would like to practice arguing with your unpleasant husband so you can finally divorce him after many unhappy decades? Matthias will eat your cake, give you his full and undivided attention, and help you brainstorm tactics for the big announcement.

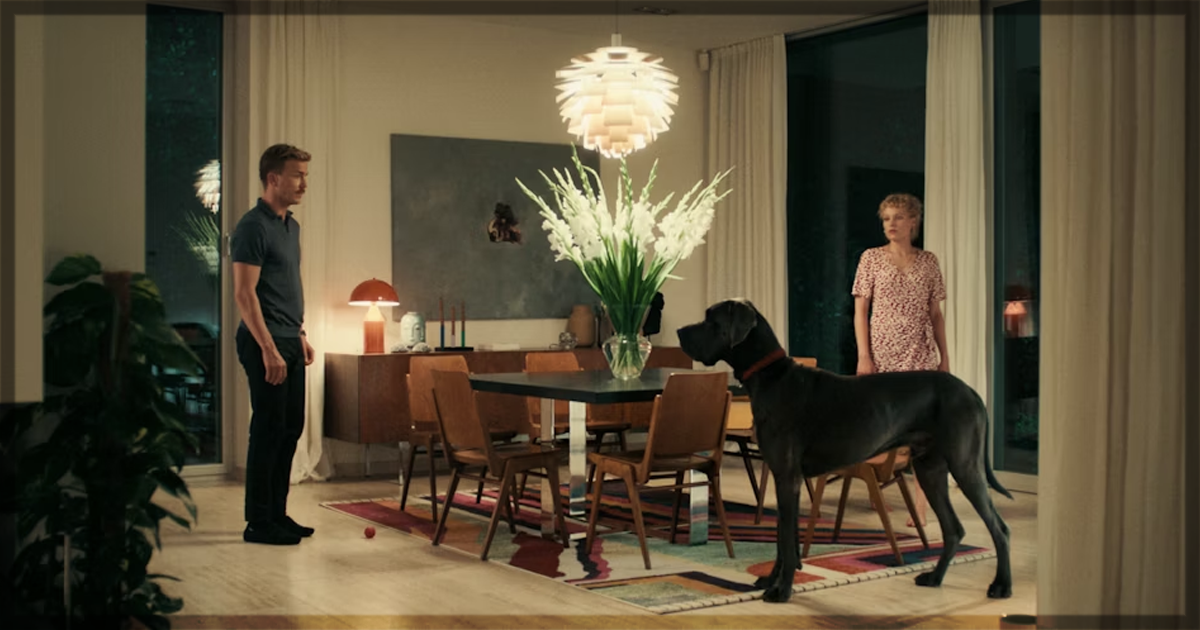

But Mattias has gotten so good at erasing his self on demand that he no longer knows his own desires. He and his girlfriend Sophia (Julia Franz Richter) live in a modernist dream home, which Matthias begins to furnish with duplicates of things he has encountered through work. Sophia retaliates by getting a great dane, an absolutely gigantic animal introduced in an initial shot of such stillness that it’s possible it is just another strange statue. But once it’s established the pet is a real thing, Matthias still has nothing to say about it.

For this and other reasons, it becomes clear Matthias needs a break. David sends him on a new-agey retreat where Matthias meets Ena (Theresa Frostad Eggesbø), a tall and friendly Norwegian who doesn’t speak German. (Quick sidebar to observe you know you’re in Austria when no one at the retreat balks at nude outdoor yoga. It’s hard to imagine anyone in the Glasgow Film Festival audience being quite so comfortable with the mere idea.) Ena is sparky and unafraid of speaking her mind, and this sets some synapses firing in Matthias that he thought he’d silenced long ago. But with Matthias’s career, the horrifying question is whether Ena is who she claims to be.

Unfortunately, the question of Ena’s authenticity is significantly less interesting than the question of Matthias’s. It is rare for art to examine how men shape their identities through the eyes of others, though there are many cautionary tale-style movies about young women so swallowed by social media their true selves no longer exist. Why are we so uneasy about asking men – especially a non-toxic man like Matthias – to confront how he has similarly erased his own identity for profit? He might not be an influencer with a ridiculous morning routine, but he’s still earning his living by pretending to be something he’s not. The shot of Matthias’s storage closet, in which all his outfits for work are stored in identical brown garment bags hung next to shelves of identical cardboard boxes, is extremely funny and also utterly horrifying. There’s no there there, by design!

Instead writer-director Bernhard Wenger is exploring what happens when a relationship is built on a lack of authenticity. It’s a pretty common assumption that the person you sleep alongside at night knows the truth about who you are and what you are thinking, and vice versa. And if that isn’t true, whether there’s been infidelity, plain old growing apart, or something else, it’s generally pretty devastating. Matthias has gotten so good at performing for his clients that he’s forgotten to be a present and genuine boyfriend to Sophia. By contrast Ena is so good at being herself in all circumstances that it’s no wonder Matthias is mesmerised by her. David’s happy, chaotic family life is another big contrast to the gleaming yet vacant modernity of Matthias’s house, but Matthias doesn’t quite understand what he needs to do differently in order to have the warm and genuine human relationships which David does. It would have been so much more interesting if the movie had focused on that mental gap inside his head, instead of the more stereotypical one between men and women.

Mr. Schuch, a huge star of the German-speaking world who came to global attention in All Quiet on the Western Front, does powerful and disturbing work here as a consummate actor who has forgotten how to stop. His reactive emptiness is compelling enough to maintain Peacock’s momentum even as the movie disintegrates around him. The bravura final sequence, which includes some of the most original nudity ever filmed, is so derivative it lands with a whimper instead of a bang. And yet despite all its flaws Peacock is somehow worth seeing. Perhaps that’s because anyone with a public and a private persona can relate to the exaggerated struggle here, which, in the current moment, is all of us.

Peacock recently screened at the Glasgow Film Festival.

Learn more about the film at the Glasgow site for the title.