Kazuo Ishiguro’s 1982 debut novel, A Pale View of Hills, is an elegant and nuanced examination of identity for post-war Japan. Kei Ishikawa’s ambitious but unsubtle adaptation can’t capture the spirit of his gorgeous writing.

The novel and the film are narrated by Etsuko, who appears in two timelines. In 1952 (played by Suzu Hirose), she is a dutiful housewife expecting her first child, and then 30 years later (played by Yoh Yoshida), we meet her again, now a widow selling her family home in England. Her inner life is a mystery, and her story is told through the perspective of her journalist daughter, Niki (Camilla Aiko).

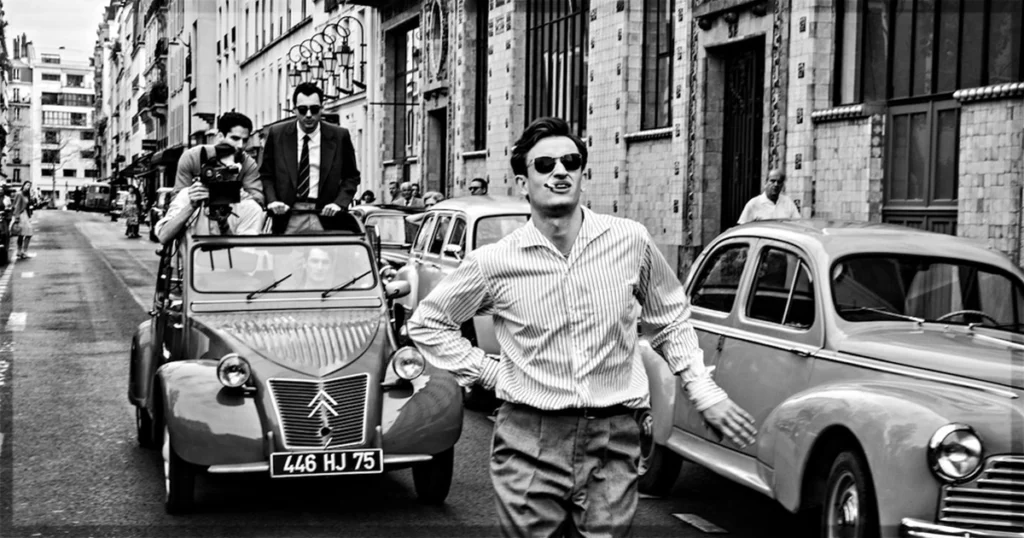

A Pale View Of Hills A Tale Of Two Cities

A Pale View of Hills is a film of two stories held together by a thin piece of string. The flashback to 1950s Japan is a sensitive tale of a friendship between two women living in post-war Nagasaki. Etsuki reminisces over her friend Sachiko (Fumi Nikaido), a mysterious woman she becomes drawn to. Etsuki is lonely and neglected by her husband Jiro (Kouhei Matsushita). Sachinko is glamorous, ambitious, and the type of free spirit that is controversial for the era. She has attached herself to an American soldier to escape Japan and make a new life for her and her daughter, Mariko, in the United States. Most people see Sachinko as an outcast, but Etsuki looks at the woman with envy.

In the more modern scenes, a now England-based Etsuki packs up her home as an empty nester. Her daughter Niki is battling her own personal and professional struggles while the ghost of missing family members lingers over her and her mother. Niki and Etsuki have an awkward relationship, which has only been heightened by the recent suicide of Niki’s sister. Overall, the characters of the 80s timeline are nowhere near as rich as the 50s strand of the plot. The unspoken life Etsuki has lived puts a wall up between the characters and the audience.

The 80s set scenes struggle to capture the same nuance. The Japanese co-production fails to understand the essence of British families. The line delivery in the more modern-day scenes feels stilted, like the dialogue has been directly translated from Japanese to English. The writers never evolved past the idea that Brits like drinking tea, country walks, and gardening.

A Film Which Struggles To Capture The Magic Of The Source Material

The source material engages with Nagasaki’s history and its nuclear attack, explaining the mood of the city and its inhabitants. These elements are largely brushed over in the film adaptation, losing a huge part of Ishiguro’s story. The film’s script never quite manages to fully portray the violence and terror of living in Japan during these years. Mariko and Sachiko’s connection to the Nagasaki bombings and the stigma it left them is brushed aside unpleasantly. This is one of the many ways A Pale View of the Hills strips away the original story, taking away much-needed nuance to create a film that is nowhere near as emotionally subtle as it should be.

A Pale View of Hills makes numerous aesthetically pleasing cinematography choices. The 1950s scenes have a warm glow of nostalgia, with DP Piotr Niemyjski shooting Nagasaki like it’s a fond memory rather than a real place. In contrast, the 1980s scenes are cooler, with Etsuki’s English home painted in dark colours and lit in muted tones. Despite all the narrative issues, A Pale View of Hills creates a melancholic atmosphere.

Ishiguro’s novel was beautifully ambiguous and played with unreliable narrators and the reader’s perception of reality. A Pale View of Hills can’t help but overexplain its purpose, spelling out all the sleights of hand and listing all the twists audiences might have missed. The sudden delivery of a final act plot reeks of trying to shock audiences, rather than letting them slowly realise the truth of the story. The ta-da nature of the writing severely lessens the required impact of the narrative trickery.

Ultimately, A Pale View of Hills suffers from the pitfalls of adapting literature for the big screen. It simply can’t penetrate the psyche of repressed and ambiguous characters to maintain the nuance without distancing the audience.

A Pale View of the Hills (Tôi yama-nami no hikari) recently played at the London Film Festival.

Learn more about the film at the IMDB site for the title.