The sophomore effort in the Napo River (Toroboro) in Manolo Sarmiento’s diptych about the local communities is La Consulta Popular, or The People’s Referendum. He focuses on the political aspect of the situation. With this film, he shifts his lenses to the isolated tribes, who decided to continue far from the big cities. The Napo River was Spain’s possession for three hundred years. The communities resisted colonization, settlement, and violence. However, those aggressions persist through the exploitation of petrol reserves. The Yasuni-ITT refers to the Ishpingo-Tabococha-Tiputini oil field. Amidst the worries of groups who defend Yasuni’s interests, the situation became a topic of public discussion in Ecuador. In 2007, the President, Rafael Correa Delgado, proposed raising three billion and six hundred million dollars to keep the oil field untouched. The value is half of the estimate of the ITT’s worth. Yet, it failed to warrant funds from the international community and immediately canceled. Thus, Sarmiento follows the last fifteen years of public discussions around the Yasuni-ITT exploration.

The director decides to approach it differently. Sarmiento goes out of the forest to focus on the political climate of what happens in the woods. The second part of the story narrates the bureaucracy and the capitalists, eager to destroy. The discourse from the administrative leadership is to profit from the ITT block regarding the destruction it may cause to Amazon. They often mention numbers and how they may head to an economic transcendence of the Ecuadorian GDP. Latin American history relies on cyclical moments to boost the economy through commodity trading. However, petrol is grander than a primary item; it aggregates political and capital power. In a sense, the oil trading allows Ecuador to negotiate its role at the diplomatic table. Yet, this capability comes through the devastation of the native land and the disruption of the aboriginal groups. Sarmiento narrates the dilemma and how it has affected the country in the last couple of years.

There is a notable digression between the two parts of the Toroboro River. The director brings a varied vision of the Indigenous; they are not portrayed directly as in part one. Sarmiento is not shooting in the Yasuni community and the IT; he indirectly narrates about them. The difference is crucial to how the film unfolds. The left bank regards the political situation and how it will affect the future. The first part, the right bank, deals with the urgency in the field. Sarmiento is not interested in connecting both parts using a pristine link. Thus, he takes time to explain how the situation is transitioning in the Ecuadorian administration. Similar to the other countries on the continent, Ecuador dealt with the inconsistency of a calm political leadership. Recently, the country suffered from coup d’etat attempts and foreign interference. The petrol fields are an integral aspect of their interest in the country. In a sense, the native tribes do not get to speak in the ITT’s exploration of their land. Thus, their desire not to get bothered and to stay in isolation is not respected.

Sarmiento glimpses how settlement violence continues even decades after the Spanish left power in Ecuador, and colonialism continues. Nowadays, the violence comes from their administration and even from the Indigenous ministry, as Sarmiento shows that she does not help the Yusanis. A group of activists, the Yusanidos, is responsible for championing their situation and claiming the stoppage of the explosions in the ITT camp. It becomes a years-long battle that analyzes the financial point rather than the well-being of the Indigenous. The film succeeds in looking at the idiocracy in the circumstances and how the arguments for exploiting the Ishpingo-Tambococha-Tiputini regions rely on the economic miracle. The promise of Royalties is grander than the future of Amazon and the Yusanis. The popular referendum in the title suffers from the manipulation of the National Voting Centre. When it happened, fifty-nine percent of the population voted to stop the ITT exploration. Yet, the conglomerate’s wish gets heard more than the population’s.

Manolo Sarmiento finalizes his saga on the Napo River by analyzing how colonialism and the Global North have their desires respected. The film suffers from inconsistencies in the structuring of the years-long documentation. Yet, it thrives in showcasing the fight of the Yusanidos and the community to stop the devastation of their homeland and the violence against the forest. Reviewing as a complete saga, Toroboro: El Nombre de las Plantas and Toroboro: La Consulta Popular are not perfect in their societal analyses. However, both parts show the Ecuadorian political and economic turmoil and how we may battle to protect the Amazon and the native groups.

Toroboro: La Consulta Popular recently played at the It’s All True Documentary Film Festival.

You might also like…

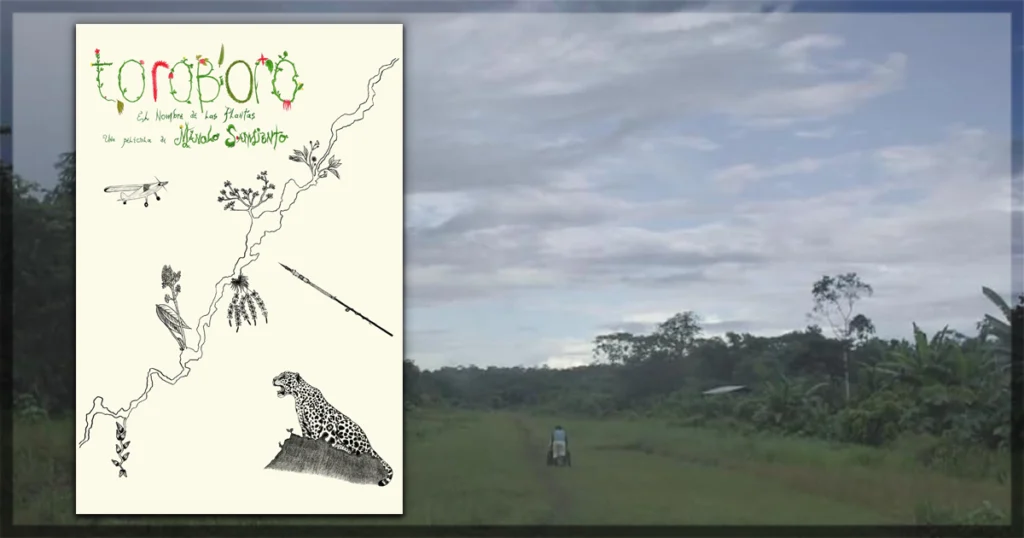

‘Toroboro: El Nombre de las Plantas’ or ‘The Name of the Plants’ Documentary Review