Nickel Boys, an adaptation of a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Colson Whitehead, has attempted to meet the current moment by telling a story of horrendous racism and child abuse with neither racism nor violence in it. This is worse than the biographies of Harriet Tubman and Martin Luther King, Jr. that I was given to read as a small child, because those books made sure I understood the evils of slavery and racism in an age-appropriate way. But Nickel Boys is a story for adults, and in this adaptation it’s for adults who prefer not to understand the evil. This makes it sanitised pablum of the very worst kind, and all right-thinking adults should be ashamed to swallow it.

For example, the American second wave feminism of the 1970s delighted in revisiting the stories of neglected and forgotten women of history. But when we confront the past, we must confront attitudes such as racism, sexism, a casual attitude to violence, and the failures of the justice system to work equally for all. These attitudes and behaviours might have been normalised, but they have never been acceptable, though the current moment (whether the 1970s or right now) does not always conquer them. What is most fascinating about our current moment is that we consider it bad manners to confront the unpleasant realities of the past. Right now the consensus is that it’s too traumatising for the present-day viewer to see the evils of the past being portrayed head-on. Slurs should be mouthed or left unsaid. A man holding a whip is threat enough. But you should not rely on an audience to be able to read between the lines, or feel that excuses could be made for any behaviours. Especially not if the audience is that of fully-grown, wide awake adults.

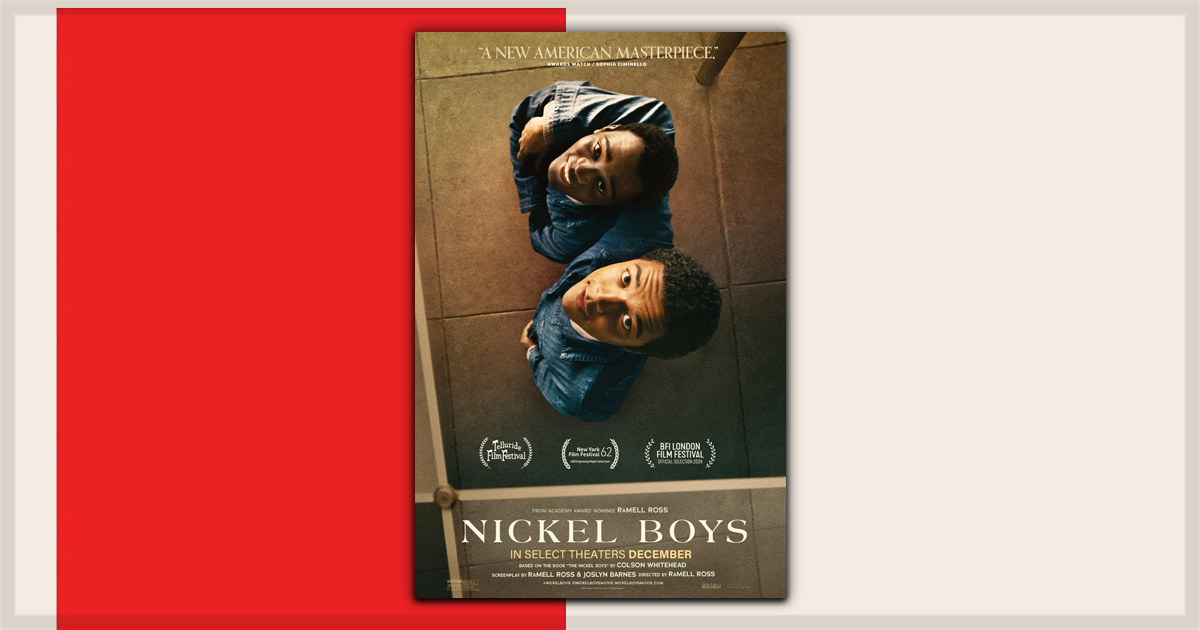

That said, there is one huge element of praise for which Nickel Boys is due. It is one of the very few movies in world cinema history shot almost entirely from the point of view of one or the other of its two main characters, Elwood (Ethan Herisse) and Turner (Brandon Wilston). They meet in their late teens when they are incarcerated in what largely seems to be a rural boarding school, where their moments are spent lying around in the grasses looking at the sky or accompanying a young teacher, Mr. Harper (Fred Hechinger making an interesting career choice), on errands around town. The fact that the place is a segregated reformatory for children who were incarcerated on trumped-up charges is largely left to the imagination. Only a brief sequence of a boxing tournament in which a bigger boy named Griff (Luke Tennie) doesn’t obey instructions demonstrates the power the teachers have and their pleasure in using that power to cause harm to the children in their care.

As shown here, Elwood doesn’t seem to understand the full weight of what his incarceration means. We aren’t even shown the process by which he is brought to the school. As time passes – months? years? – Elwood continues to believe some polite conversation will end up with him restored to the world and his rightful place in it. Turner is a bit wiser and more cynical, but unable to bring himself to shake the wool from Elwood’s eyes, even when he meets Elwood’s grandmother (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor). Hattie raised Elwood right, is bewildered by the circumstances he’s been caught up in and cannot seem to understand what she’s up against either. This wide-eyed ingenue act might work from a white character caught up in these circumstances, but 1980s America, when the story is largely set, was not a post-racial time. It beggars belief that any black family would be so unaware of how the deck is stacked against them even if they are too resigned to fight.

The worst part of all this is that The Nickel Boys was based on the real-life discovery of unidentified bodies at a reform school in Florida. There have been some excellent recent movies and documentaries out of Canada and Ireland about their similarly shameful history. In Canada, Night Raiders and Sugarcane have showed how boarding schools for Indigenous children tortured and abused them, while the Magdalen laundries where inconvenient Irish women were incarcerated have been laid bare in Pray for Our Sinners and Nothing Compares. Even the just-released Small Things Like These, a pleasant fantasy about standing up to power also set in the 80s, has a better sense of the stakes as it shows a man harming his livelihood, family and future for an unknown teenager. But the director of Nickel Boys, RaMell Ross, who co-wrote the screenplay with Joslyn Barnes, is an American.

Based on his work here, it feels like he and Elwood share the same belief that no one would be racist if they understood that racism was wrong. It’s touching to see any adult still have this belief, but the regrettable truth is that the world is not that kind. If the movie had hewed only to Elwood’s point of view, instead of flicking back and forth between his naïve perspective and that of the wiser Turner, Elwood’s awakening would have been incredibly dramatic. Instead, after establishing the rules of the film – our first glimpse of Elwood is in the reflection of Hattie’s iron – Ross and cinematographer Jomo Fray break them. They break them for a reason explained by the final plot twist, but the ramifications of that twist are once again only hinted at instead of faced directly. This will probably leave many audience members wondering just what the fuss was about.

To leave an audience to atrocity thinking the atrocities weren’t so bad after all is the first step to denying those atrocities ever happened. And while this might be the right attitude to take to protect the innocence of children, it is the worst possible one you can take as an adult. It is shocking that, by pandering to the best intentions of the modern moment, Nickel Boys has turned into a feeble apologia for the worst kind of American evil. Then again, we all know what the road to hell is paved with.

Nickel Boys will play in US theaters this weekend.

You might also like…

‘Small Things Like These’ Review: Cillian Murphy in a Conversation Starter (Berlinale)