Meeting with Pol Pot is very loosely based on a memoir by an American journalist named Elizabeth Becker, who was at its first screening at the Cannes Film Festival. It must have been a very strange feeling to see a fictionalized version of some of the most important events in her life, which hopefully provided an emotional, if not a practical, truth. As in Never Look Away, a documentary about a war journalist, director/co-writer Rithy Panh chose to re-enact some of the unstageable events with dioramas in this fictional film. Somehow, little dolls and a sense of childhood craft can express a horror that more realistic depictions of which would render nearly unwatchable. But this movie, which takes pains to emphasize that it is not a documentary, is also not directly about the horrors of the Khmer Rouge. Instead, it focuses on the risks journalists must take to discover the truth and is a keen reminder of the importance of moral courage.

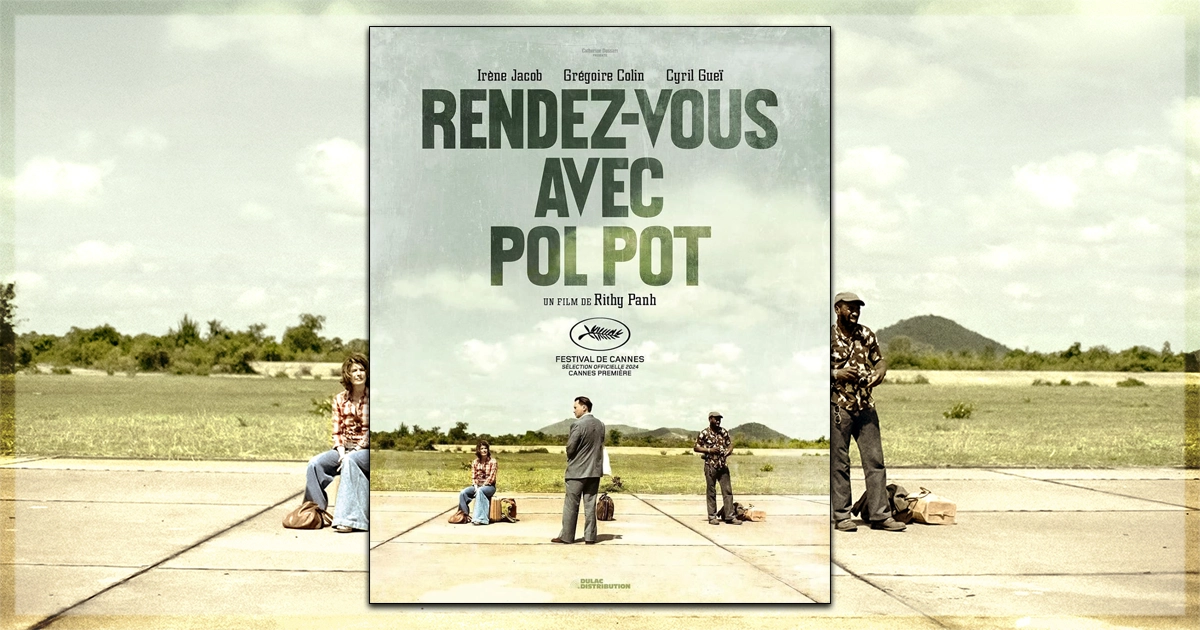

When the three Westerners are left by themselves in a deserted airstrip somewhere in Democratic Kampuchea, they really only know they haven’t been landed where they originally planned to go. But all are stoic, and used to discomfort. Paul (Cyril Gueï) is an accomplished war photographer, and Lise (Irène Jacob) is an experienced journalist who’s worked in Cambodia before. Their fixer is Alain (Grégoire Colin), an academic who befriended many Cambodian students when they were studying together in Paris and whose long-ago friendship with Pol Pot is the reason they have been allowed into the country.

Lise is pragmatic about her chances of learning the truth about people’s ordinary lives under the regime, especially since all their meetings are micromanaged and translated by an interpreter (Bunhok Lim) who is clearly a mouthpiece parroting the party line. But she’s determined to do her best, paying careful attention to everything she sees, even as Paul chafes against the many soldiers who are supposedly there for their protection.

Lise has a separate bedroom to the men and was provided a small hatchet as a welcome gift, but all of them are locked in overnight and never allowed to speak with anyone without their minders present. This seemingly disturbs Alain not at all. He glides around the tours and the scenery provided with a calm confidence that eventually his old friend the dictator will grace all of them with a catch-up. The interpreter is clear that any such visit, should it actually happen, will be with little notice, the better to keep ‘Brother Number One’ safe from his enemies. Lise shrugs and works over her typewriter as Paul paces.

Mr. Gueï, Ms. Jacob, and Mr. Colin manage to convey a great sense of professionalism, and their characters all respect each other even if they don’t like each other very much. In moments of crisis, the three Westerners also automatically stand together even when they are very angry with each other’s choices.

It’s Paul who first breaks the weary truce with their minders when he sneaks away from an official visit to explore a village they have been told is abandoned. The truth is much worse, and the fact that Paul might have witnessed it has the minders beside themselves with rage. This act of Paul’s is good journalism but utterly stupid and dangerous on a personal level, and the three Westerners have a few heated debates about whether their first responsibility is to the truth or to keeping everyone alive. Everyone including anyone non-official who crosses their path, of course.

Here’s where the fear actively kicks in, within the Westerners as well as the audience, as it becomes apparent that even the most innocuous interaction can lead to immediate execution for somebody. But then something else goes wrong, and things get horrible indeed. The fact that some of this fear is expressed in those hand-carved dioramas almost makes it worse because you don’t need to look away.

Cinematographers Aymerick Pilarski and Mesa Prum convey the oppression not only through the heat but through the unbreakable distance between the Westerners and the others they encounter when in human or artistic form. The scenes of soldiers on the airstrip, either whizzing around in their trucks or carrying a papier-mache elephant for a dance, hammer the points about drudgery, militarisation and the panopticon without overdoing it. The ending is bloodthirsty and brutal, too.

The fact Ms. Becker lived to tell the tale is the only emotional respite, but that doesn’t mean much. Nowadays, the smartphones of the people who live there would be the journalistic eyes on the ground, but Meeting with Pol Pot argues that even only shills and quislings, if they have a first-person perspective, are better than nothing. The fact we rarely have to question this anymore is a marvel of the modern world. More than anything this is an appreciation of those people who went as close to the killing fields as they could, and a reminder that this kind of professional bravery remains an important and valuable skill to tell the truth and shame the devil.

Meeting with Pol Pot (Rendez-Vous Avec Pol Pot) recently screened at the Cannes Film Festival.

To learn more about the movie, visit the Cannes website for the title.

You might also like…

‘The Damned’ Review: A Quietly Remarkable Film (Cannes)