Musical biopics consistently earn a reputation as a simple path to awards seasons and other accolades. In recent years, there have been examples in Bohemian Rapsody, Maestro, Elvis, and The United States vs. Billie Holiday, among others. It is a genre that has been repeating itself constantly and delivering mediocre films to the public. However, Rich Peppiatt’s Kneecap deconstructs the recent trend of generic and shallow musical portraits. In its basis and conceptualization, Peppiatt’s script (co-written with the trio) distances itself from the chronological presentation of the group. He first presents the political and social context of that universe. It is essential to state that even though it discusses the Belfast political landscape, Peppiatt’s approach is to point to the nonsense and not take it too seriously.

In the first minutes, it establishes the basis of the film, visually and textually. The violent history of Belfast with the English colonization through archival footage over a highly ironic voice-over by Mo’Chara, who plays a fictionalized version of himself. His and Móglaí Bap’s relationship with party drugs. Then, DJ Provái, a music teacher in a Catholic school, was introduced. He serves as a translator to Mo’Chara in prison, as he refuses to speak English and only answers the interrogation in Irish Gaelic. Their connection deepens when Provái hides Chara’s notebook with drugs and lyrics. On his way home, he thinks about melodies and produces instrumental beats for them, suddenly becoming the Kneecap.

In less than twenty minutes, the film presents its three main pillars: the rap group, the Irish language, and the fight against the oppressive British police. While it has a comedic tone and constant jokes about sex and drugs, the film explores a political thread about modern Belfast. It distanced new generations from Gaelic. The high usage of medications is because of trauma and a lack of public politics that think about that community. And the clash against the R.A.A.D (Republican Action Against Drugs).

The elements involving drugs, the consumption and the buying of it, remind a bit of Danny Boyle’s classic, Trainspotting. It is more similar in terms of the visual representation of the Ketamine effects, for example. A performance on stage choreographed as puppets and an invitation to send a tape for the radio while they are claymation characters. It adds more to the absurdity that is frequently present in the film.

The tone makes Kneecap fresh

The tone here is what makes the film a fresh musical biopic. The script mixes gangster film tropes with the rise to fame. But it never leaves behind the political layer that the Gaelic plot adds. There is a subplot involving Michael Fassbender, who plays their disappeared rebel father, and it has a thriller approach. But when it returns to Belfast, it blends with the nonsense in action scenes. And it is what succeeds in the movie.

The film shows the violence in a kinky way, not as a fetish for violence, but as a turn-on and a manner of resistance, specifically in a scene involving police brutality. The kinetic drug sequences have resemblances to trafficking movies, but the film maintains a comedic tone and stays true to the overall plot. All of those scenic constructions are done with dynamic camera movements, colorful backgrounds that emulate the colors of the Irish flag, and the use of neon when performing, visually an enigmatic look that contributes to the whole conceptualization.

The film even suffers from rhythm in the second half, while it needs to give the public a reason to end the band and prepare for the climax. Some characters merely support plots, like Provái’s love relationship with a political activist, Mo’Chara’s girlfriend, and the boy’s mother. The film rushes to achieve a conclusion. It does not compromise the ideas the film tries to work on. Despite its disproportionately rushed last act, the final thirty minutes blend the film’s best elements.

The silly jokes, kinetic action scenes involving the R.A.A.D and the band, and great songs. The songs are mostly from their debut record released earlier this year, Fine Art—an album that talks about mental health, the lost youth of Belfast, violence, and drugs. And the film transitions to the visual media using what the film format can provide. Camera angles emphasize feelings, the film cuts to improve emotional involvement and frame compositions. It combines the film format with their outstanding record and enhances the quality of the film.

Final thoughts on Kneecap

Kneecap experiments with its confusion. Belfast, society, and the trio are confused. British colonization and soft power pressed them and continue to affect them until this day. But it is also a portrait of how the new generation, the first-born after the country’s independence, deals with the problematic traits that the settlers left to them. It uses comedy to deal with the music industry, drugs, language, and cultural aspects of a society where it is learning about the taste of freedom.

Kneecap debuted at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival in the NEXT section. It was the first massive acquisition of the festival by Sony Pictures Classics in the United States.

Kneecap is now in limited theaters.

Of note, Ireland selected the film as their submission for the Best International Feature Film for the 2025 Academy Awards. You can learn more about Kneecap at the official Sony Pictures Classics site for the title.

You might also like…

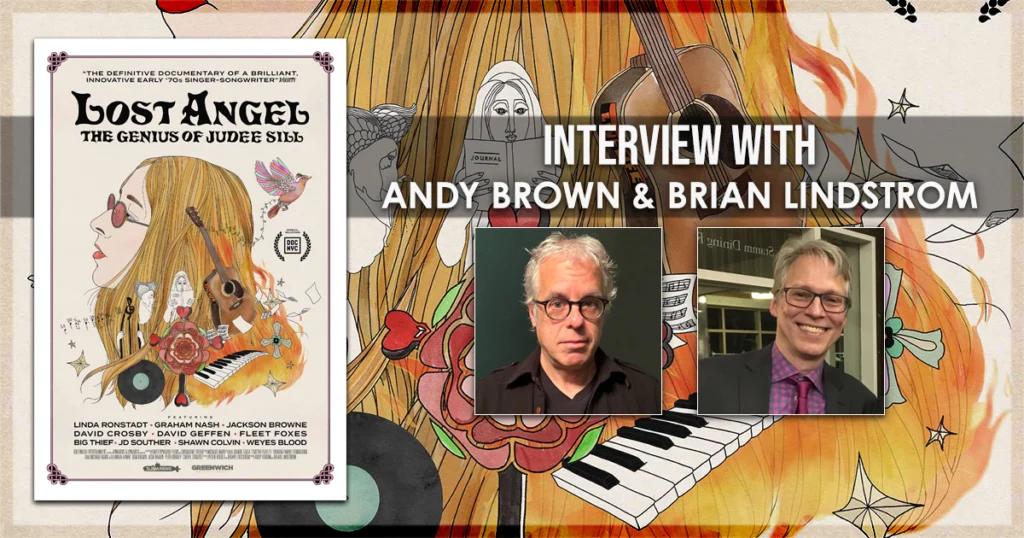

‘LOST ANGEL: The Genius of Judee Sill’ Interview with Filmmakers Andy Brown & Brian Lindstrom