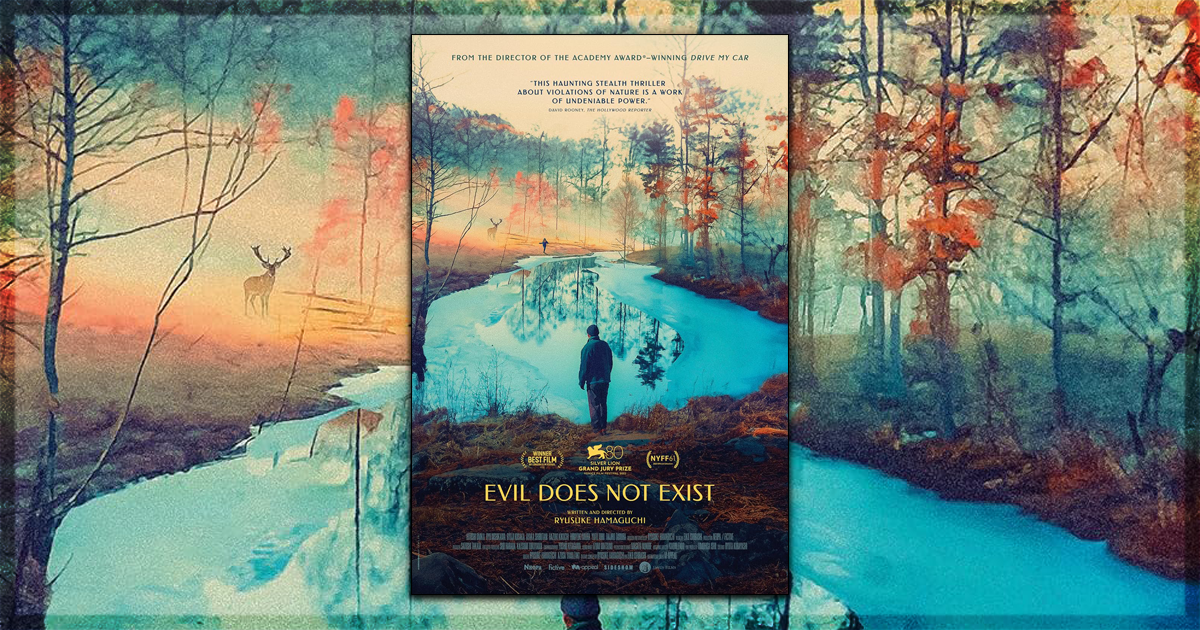

Ryusuke Hamaguchi has never made the same film twice and has always approached each project he takes on with a different lens and perspective on what he did previously. It’s highly apparent just by watching his Oscar-winning feature, Drive My Car, a nearly three-hour-long, slow, and meditative drama, and his latest project, Evil Does Not Exist, back-to-back. The first and most immediate thing that comes to mind is the 106-minute runtime, much shorter than Drive My Car’s 179 minutes (or Happy Hour, which clocks in at a whopping 317 minutes). The second thing that jolts our interest is how Hamaguchi begins his movie with underneath shots of the glades, juxtaposed with his opening credits, as he indirectly tells us how nature will have a massive place in his movie.

Evil Does Not Exist’s Story: A Village’s Struggle Against Development

It takes about half an hour before we begin to understand the story, focusing on Takumi (Hitoshi Omika) and the rest of the Mizubiki village’s life being upended by a potential real estate project that could deter their quality of life. Developers Takahashi (Ryuji Kosaka) and Mayuzumi (Akaya Shibutani) present the village as a ‘glamping’ project (“glamorous camping,” as they call it), which they hope will boost the local economy and make more people want to visit Mizubuki.

However, villagers are concerned about the project’s long-term impact on the town’s fragile environment and ecosystem, whose spring water is directly used in all areas of their lives, particularly in making the broth for Mizubiki’s only noodle shop. After hearing their concerns, Takahashi and Mayuzumi head back to town and believe their complaints aren’t unreasonable. However, the head developer (Yoshinori Miyata, zooming in from his luxury car with zero perspective on what occurs in the village, à la Nina Hoss‘ Doris Goethe in Radu Jude’s Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World) wants them to aggressively begin construction on the project as soon as possible since they have limited subsidies from the government.

Their boss now tells them to hire Takumi as a mediator to help them persuade the villagers to think the glamping project is a good idea, but they will soon find out about the ways of the village and how their project is not compatible with the fragile, almost ethereal environment that lives within Mizubiki. Like Jude’s Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World, Hamaguchi deals with the effects of a society whose only goal is to reward the one percent and leave everyone else behind. However, in this case, the one percent will never be able to achieve their goals since the community built around Mizubiki will resist any attempt at upending the town’s rich and biodynamic ecosystem.

That doesn’t mean they won’t try – and they sure do – as Hamaguchi depicts drawn-out scenes of clueless Takahashi and Mayuzumi attempting to tell the population that the septic tank will have no effect on the village’s pure spring water (only “minimal pollution,” as the boss eloquently says during the Zoom call, with zero real-world knowledge of what’s at play), or that the project will be done with environmental protection in mind, even if they themselves know it’s a lie. Takumi is right not to trust them when they eventually reach out and have lunch together, which is when the tension dials up, and the movie becomes far more interesting than it previously was.

The visual look, in particular, sees Hamaguchi at his most evocative, with images and transitions directly recalling Jacques Perconte’s Bois Des Montifaut, Forêt Des Bertranges, as cinematographer Yoshio Kitagawa slowly examines the fragile nature of Mizubiki, with lots of contemplation in between some of the film’s most dramatically powerful scenes. In fact, the film’s best sequences frequently observe nature through different parts of the day, whether in the early morning or, as the movie ends, so does the day. These strikingly beautiful shots bring us closer to the planet’s most primal needs: the earth’s dirt, the life of plants (wild wasabi in one of the film’s most breathtaking moments), and the purity of water.

Abrupt Ending and Missed Opportunities in Evil Does Not Exist

As we get drawn into the stories of Takumi and the developers, Hamaguchi takes a swift, jarring, dramatic turn that, while compelling on its surface, doesn’t develop it to the fullest. In fact, as soon as that turn occurs, the movie ends five minutes later. Of course, we understand that most of the story has been told, as the power of community will ultimately prevail against the evils of capitalism, but there seems to be far more meat around the bone than Hamaguchi thinks there is, therefore making its ending feel more underwhelming and half-baked than it should be.

But it doesn’t deter itself from the immense power brought by Omika’s magisterial lead performance, an incredible display of repressed emotions that makes the character’s final decisions far more impactful than Hamaguchi initially introduces within the protagonist’s surface. Coupled with Eiko Ishibashi’s haunting, almost spiritual, musical score, and you’ve got yourself an atmospheric eco-thriller that is always on the forefront of challenging audiences with its bold narrative swings, vivid cinematography, and sharp editing but doesn’t go as deep enough as it should. But with Hamaguchi never making the same movie twice, his next project should be met with great anticipation, and I’ll be seated for whatever he does following Evil Does Not Exist, even if its ideas didn’t come together as fully as they did with his previous two efforts, Drive My Car and Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy.

You might also like…

‘Cobweb’ Review: Kim Jee-woon’s Black Comedy on the Horrors of Filmmaking