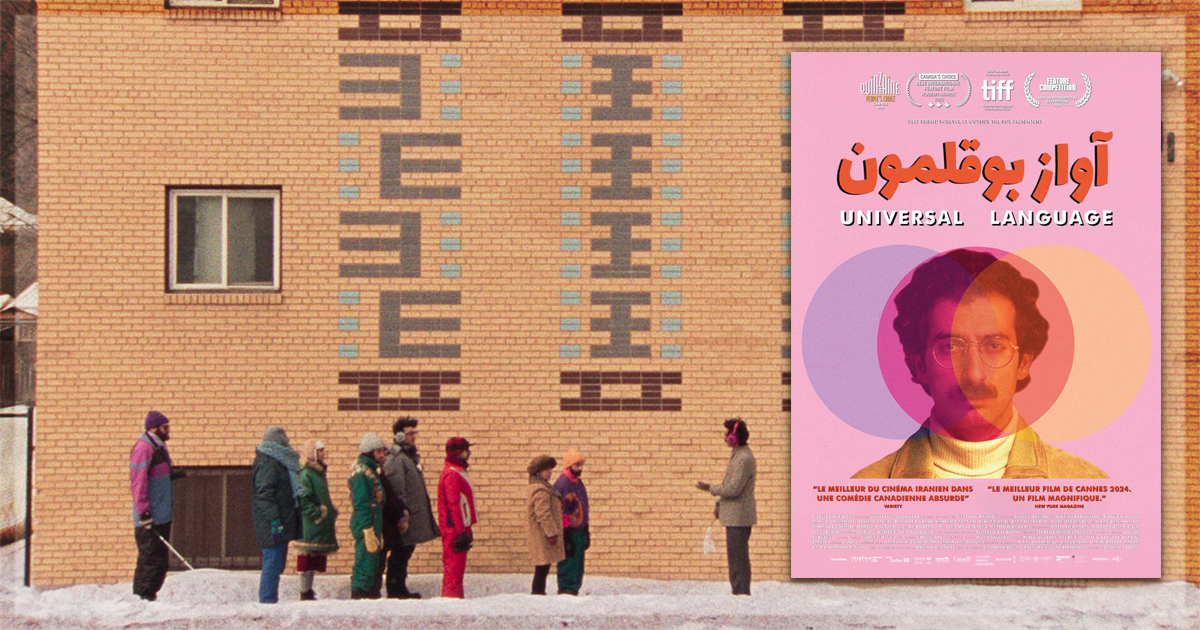

Universal Language, the latest from Canadian director Matthew Rankin, follows Abdolreza Kahani’s A Shrine as another delightful Iranian-Canadian comedy hitting the 2024 international film festival circuit – a welcome trend, judging by the quality of these two excellent films. Written by Ila Firouzabadi, Pirouz Nemati, and Rankin, a vignette structure unfolds around an alternate universe Winnipeg that seems to have frozen in the 1980s, though the time is never definitely specified (events from 1978 and 1958 are cited). In reality, Winnipeg is an English-speaking city in the province Manitoba, though it has a substantial historically French-speaking population. In Universal Language, the language in question is Farsi. There is no explanation of this left turn from the world we know; frankly, there does not need to be.

In one of many interwoven plots, friends Negin (Rojina Esmaeili) and Nazgol (Saba Vahedyousefi) divert after a santoor lesson to go on a snow-bound quest for an axe to free some cash frozen to the ground – dreaming about the socks they can buy once the bounty is theirs. In another, a tour guide named Massoud (Pirouz Nemati) leads a bemused flock of tourists around Winnipeg sites, chief among them a briefcase left abandoned and unopened on a sidewalk bench since 1978, since given UNESCO World Heritage status for the “inter-human solidarity” its contents, still secret from an unspoken pact between the residents not to open it, represent. The party is trailed by Omid (Sobhan Javadi), a classmate of Negin and Nazgol who dreams of taking Massoud’s job – but first and foremost, he needs new glasses, a wild turkey having stolen his. Then there are the disappointed teachers, the unruly students, and a man dressed as a Christmas tree.

Uniting all is the tale of a disappointed worker Matthew (Rankin himself) who has journeyed home to visit his sick mother and finds himself tangential to the vibrant, offbeat local activities that come and go through Universal Language. A brief picture of Montreal before Matthew sets off on his journey is not nearly as charming, though it also features a live turkey – this time taking public transport rather than stealing glasses.

The resulting film blurs relationships to time, place, and each other just as the snow and nondescript concrete architecture washes Winnipeg out. This is not a failure of the design team; after spending time in this deliberately drab world, its tiny beauties become apparent. This background and disorientation only serve to let the charming conundrums of Winnipeg’s fictional inhabitants come to the fore. In the film’s final third, the timelines and threads Rankin has been painstakingly spinning and crossing weave themselves into a coherent narrative whole, rewarding patient viewing with a powerful reveal.

In style and tone, Rankin nods to the greats of modern Iranian cinema such as Majid Majidi, Jafar Panahi, and Kahani (Universal Language and A Shrine would make a great double bill: one a flight of fancy, the other a wry morality tragicomedy), but a Universal Language reference point for viewers not especially well versed in Iranian cinema or in Rankin’s previous work is Wes Anderson – another master of the interlocking vignette and dry comedy. The retro billboard and television advertising is of a similar flavour to his Asteroid City or Grand Budapest Hotel, with a distinctly Canadian twist. Long shots that take in wide swaths of snow, brick, and concrete, almost silhouetting the characters’ small figures against such unforgiving natural and man-made forces, evokes Anderson’s framing with less artificial symmetry. Lastly, the deadpan dialogue delivery and slight over-explanation of scenarios, externalising thoughts and relationships, strikes a similar note to Anderson’s best works – notably in the way children are written and presented as beings with their own chaotic logic and definite agency. As in Anderson’s best, the performances are perfectly calibrated to the quietly madcap world and the equal weighting of low and high stakes.

Rankin’s previous feature, The Twentieth Century, took an anarchic, irreverent, surrealist view of Canadian history and one of its most (in)famous and long-serving Prime Ministers, William Lyon Mackenzie King. Eschewing this grand, sweeping scope and satire of a colonial government to turn his eye instead to an alternate history and culture, one where the primary language is Farsi (including on Tim Horton’s signs) and the portrait of Louis Riel, a political leader of the indigenous Métis people and the founder of Manitoba, hangs in the school instead of the Queen. The tawdry, bawdy, overtly theatrical Twentieth Century is perhaps colonialism at its most hypocritical and self-serving, and Universal Language embraces a gentler aesthetic in its offbeat multicultural celebration. It is a genuine delight and a tonic in close-minded times. Poking fun at French Canadians might be the only place where both films align.

Universal Language is well worth seeking out – a strange little wonder of storytelling that creates its own world a few degrees removed from our own with heartfelt humanity. It recognises and revels in the joys of community without ever tipping into saccharine sentimentality or undercutting this open-hearted approach with cynicism. Rankin has a strong directorial voice and clear command of style, and his next feature could be a complete surprise. Whatever its tone or topic, it is eagerly awaited.