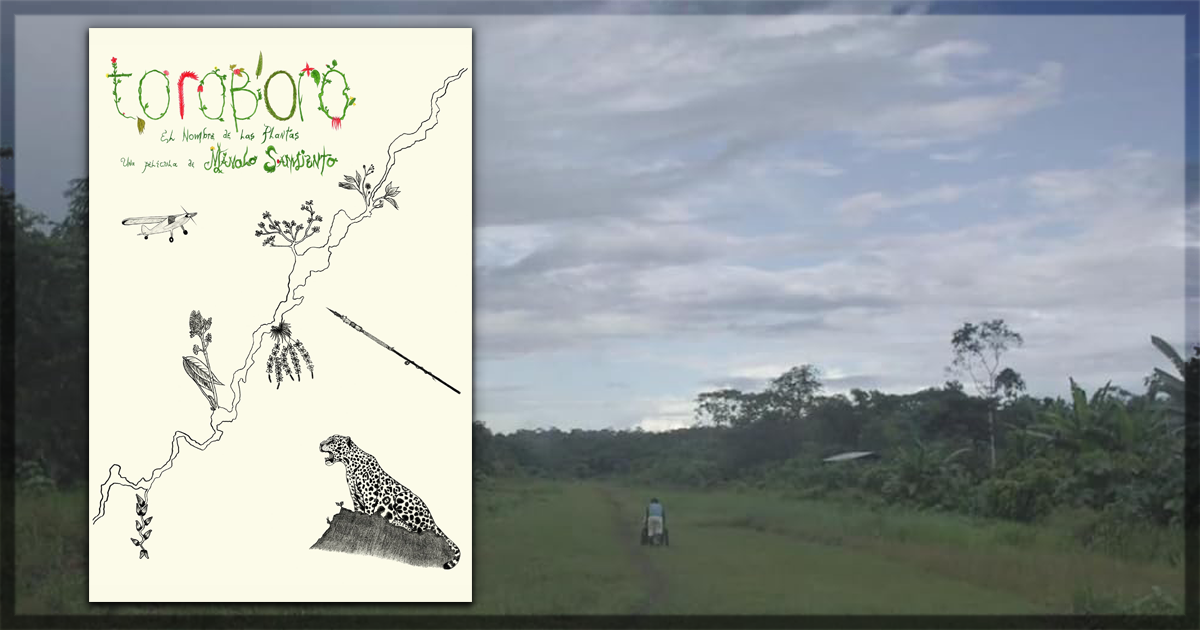

The Ecuadorian director Manolo Sarmiento is a crucial figure in the local documentary community. He is the co-founder and executive director of EDOC, Encuentros del Otro Cine, a singular festival for Ecuadorian cinema. Sarmiento produced a diptych, a two-piece work on the native people of the Rio Napo. The indigenous tribes call it Toroboro. The director presents the first part as El Nombre de Las Plantas (The Name of the Plants). It is a cut on the botanical richness of the forest around the river and its protectors, specifically the ones on the right bank of the margin, the Waoranis. In this sense, he dives into various species that serve multiple purposes in their daily lives. However, as long as he develops the project, the film goes through a different journey. It broadens its horizons from the botanical report to an analysis of the political and economic aspects of how the government deals with the native groups.

The Waoranis live amidst immense reserves of petrol in the territory. Their ancient land has the potential for grand enrichment of the oil companies and investors. In this sense, the El Nombre de Las Plantas encounters a central and typical conflict in the Latin American historical canon. It faces the interest of international companies in exploring natural resources. Other countries on the continent have had the same experience before, which would be one of the reasons for the coups d’état organized by the United States in the 1960s and 1970s. The communist threat would have behind it the intention of exploring the land and enriching the global north in the multipolar era of capitalism. Sarmiento centers his discourse around the danger of the explosion to find the petrol and how it may exterminate plenty of species of the Ecuadorian Amazon. His film is an urgent look at the work of those cataloging the almost unknown species. In actuality, only six hundred and twenty-five are in the record.

The director proposes the re-encounter of a duo of researchers and the community. The botanists and doctors Carlos Céron and Consuelo Montalvo organized an expedition in the 1990s to the Quehueiri-Ono precinct. The study would focus on mapping the species and their utilities; however, the project would shut down due to a lack of funding. It unites the doctors and the group that welcomed them almost forty years ago. The segment engages with the emotional bonding between the two universes: the elder Indigenous and the university professors. At the same time, a gap separates them, but their love for the forest brings them together. Sarmiento documents the bond of the groups, looking forward to protecting the jungle from exploration and the extinction of native species.

The director explores the complexity of Toroboro’s right bank. The structure is adequate for the discovery of the process. It is clear how Sarmiento modulates his film as he finds newer details for his thesis. The necessity of a two-piece division is apparent as the film leans toward its conclusion. The urgency of the economic investigation is greater after the exposition of the deal negotiation between the oil companies and the acre owners. They pay sixty dollars for each acre explored, a price that is ridiculously small compared to the financial potential of the petrol business. The urge to catalog the native plants is inherent in the contamination and destruction that the oil business leads to. Sarmiento narrates the worry and pain of those losing their ancient land and fearing assassination by confronting the moguls who make billions by invading their homes.

The expansion of the discussion connects the two parts of Sarmiento’s work: the left and right banks of the river. In El Nombre de las Plantas, he presents the ecological function and cruciality of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Meanwhile, he digs into the petrol exploration to focus on the government’s contempt for the original tribes, such as the Waoranis. It is an introduction to his Rio Napo saga and a warning on the fate of the reserves and the Amazon. The abundance of documentation and conversations bloat the core of the film. It carries plenty of comments and discourses that do not unfold totally. Therefore, the ending feels incomplete, as most of the parts do. But Sarmiento establishes thematically his intentions in the first part.

In El Nombre de Las Plantas, Manolo Sarmiento condenses his years-long footage about the oil’s exploration of the Toroboro/Napo River in a diptych. Besides the constant feeling of incompletion of the work due to a second part that finishes the discussion, he proposes. Sarmiento welcomes us to the Waorani community and familiarizes the audience with the paramount significance of the plants in the ecosystem. Hence, he goes beyond a simplistic nature documentary to dive into the environmental policy in Ecuador.