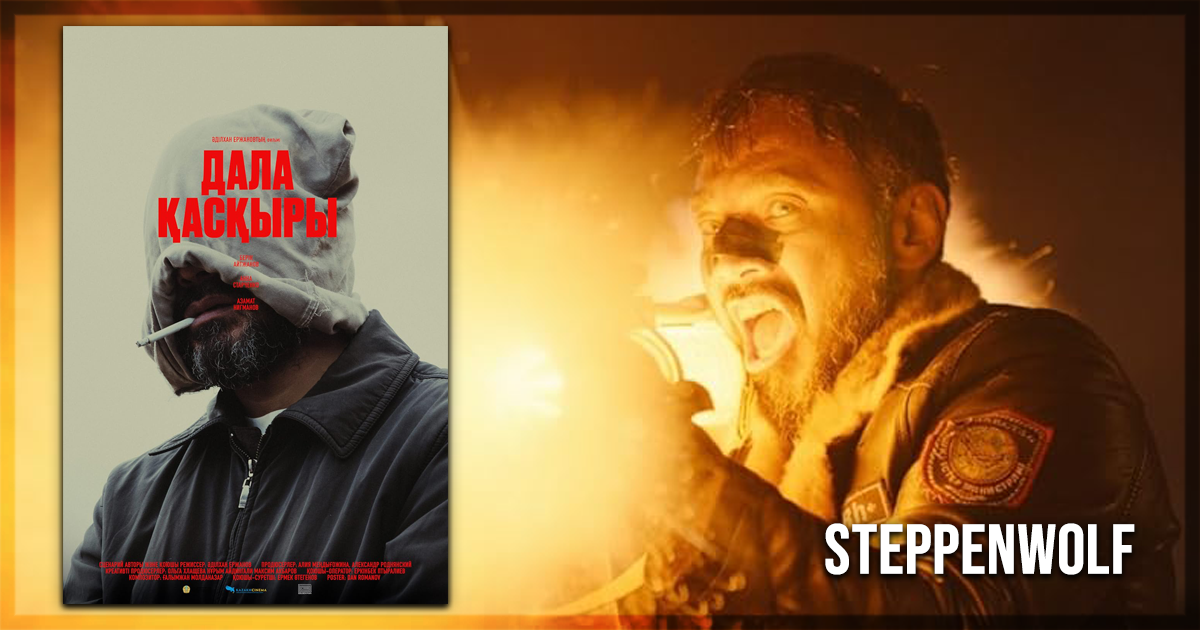

After opening with a quote from Herman Hesse’s famous novel of social and spiritual isolation, Steppenwolf – the latest from director Adilkhan Yerzhanov – moves away from the German-Swiss author’s work that shares its name into another interpretation of “a wolf of the steppes.” This takes the form of an anarchic dystopia on the edges of a fraying civilization. Here, a near-future Kazakhstan saw no economic regeneration following its post-Soviet miasma, instead diving headlong into a bloody police state that enforces its rules with mindless torture. The roving gangs and warlords do not offer a better model of society, merely an alternative allegiance offering its own slim chances of survival and supremacy on the steppes.

If it all feels a little extreme, it is, and unapologetically so. Steppenwolf opens with a roving band hosing and scrubbing blood off (presumably stolen) police shields in preparation for another raid; barely a few minutes later, at the “official” police headquarters, a complainant is not only dismissed but tortured with a rotary blade by the station’s most ruthless investigator (Berik Aytzhanov). Known as “The Steppenwolf,” he is a rehabilitated convict – if working in service of state violence can be called such. As these factions inevitably and violently clash, Tamara (Anna Starchenko) wanders into the fray. One minute her son Timka was outside their small cottage on his swing; the next he had vanished as if into thin air. The Steppenwolf makes a bold bid for his life when about to be shot by the marauders: he tells them that Tamara has lots of money and she will pay handsomely for the safe return of her son. Tamara, shaken, does not contradict him. Now the Steppenwolf must keep up this ruse long enough for him to stay alive, though his allegiances shift the more time he spends with Tamara. Perhaps it is predictable that the plot develops into this unlikely pairing against the world, but the journey is bleakly satisfying and provides room for other surprises along the way.

Yerzhanov situates his world in the not-too-distant future rather than a full-blown dystopia; for instance, CCTV cameras still work and provide the first step in tracking Timka’s movements. In one section, a curfew announcement blares over loudspeakers as the pair picks their way through burned-out cars and half-standing buildings. The apocalypse is in progress, not a thing of the past.

In the Steppenwolf, Yerzhanov and Aytzhanov create an antihero whose charisma keeps audiences interested, if not wholly on his side. The film’s only comedy comes from his twisted sense of nihilism, but unlike many a modern supervillain, this is unforced and often genuinely amusing. Perhaps (to paraphrase Karl Marx) his convict past was the Steppenwolf’s tragedy, and this anarchy is the second time as farce. Lest the audience forgets his roots, however, he never develops a distaste for the merciless violence he dishes out as long as the price is right. His moral code may have shifted towards something softer in his attachment to Tamara (though this also has moments of nastiness), but it just refocuses this destruction and sociopathic detachment rather than changing them.

The portrayal of Tamara is ambiguous, sometimes uncomfortably so. At first it is unclear whether she is disabled or has a speech impediment, but as the film progresses an overarching picture emerges of a woman traumatised by an unspecified past – pushed past fight or flight to the freeze reaction in all scenarios. Considering the violence on show throughout Steppenwolf’s run time, that past does not need to be elucidated. Starchenko’s performance is mesmeric, her eyes always alive even if she cannot find the words to express herself. Without giving away the film’s conclusion, her clearly stated motives and desires fuel the power – and unexpected satisfaction – of the film’s conclusion.

Yerzhanov has a keen eye for visual influence and The famous doorway shot from John Ford’s The Searchers is evoked twice (and explicitly referenced by the director in interviews), centering Tamara’s search for her son within the earlier film’s similar kidnapping narrative, and the Kazakh landscape’s harsh beauty and variety in sunlight, fog, and darkness adds its own wild character to the battles and ambushes. There is something of Mad Max in this post-apocalyptic vision – without so many creative names and decked-out vehicles, but with an equal ruthlessness and cultish factionalism – and these grasslands and rolling hills are every bit as atmospheric and unforgiving as Australia’s deserts. It is common for many “preppers” (those who stash cans and weapons in preparation for collapse of government or civilization) to idolize an isolated life and imagine they can build their own fortress, but the task looks to be all but impossible in Steppenwolf. Any sense of community was destroyed with ease if it even existed when whatever precipitated these events broke down in the world.

With its unabashed gore and only the darkest comedy, Steppenwolf is often a difficult work to stomach but Aytzhanov’s and Starchenko’s performances find light and humanity that reward the journey. Part gleeful slaughter, part righteous Western, its morals are hazy and its vision uncompromising. It may fall short of The Searchers (as most films do) but it is one of the more memorable, arresting, and fully-rounded dystopian pictures in recent memory.

Steppenwolf recently screened at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

Learn more about the film at the Edinburgh website for the title.