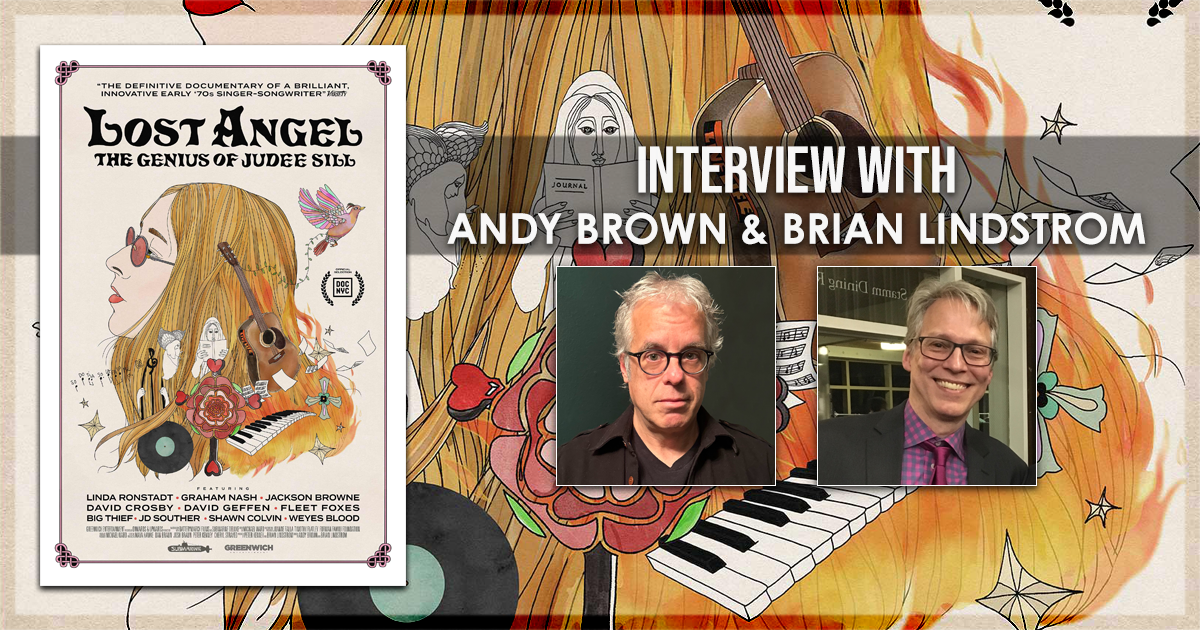

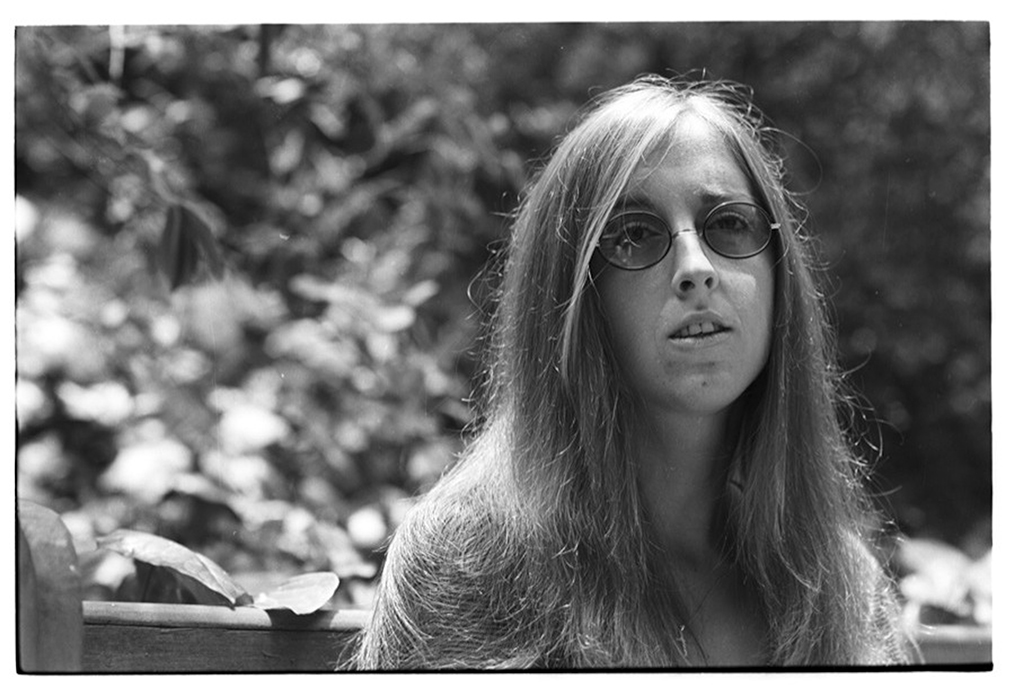

Judee Sill is the musical icon that time has forgotten. A new documentary from filmmakers Andy Brown and Brian Lindstrom seeks to change that. LOST ANGEL: The Genius of Judee Sill is the definitive history of the female vocalist and musician. Sill was a transformative artist but also had a troubled life that tragically ended too soon. And although she counted counted Linda Ronstadt, Joni Mitchell, and Jackson Browne among her contemporaries, much of her music and her story were lost to time. If you’re a fan of folk rock or even just appreciate great music, this film is essential to watch. Through interviews with friends who knew her, gorgeous animated journals, her own voice, and other archival material, LOST ANGEL breathes new life into the story of Judee Sill.

Filmmakers Andy Brown and Brian Lindstrom sat down with me over Zoom and gave me an inside look at how the documentary came to be. The two shared their journey to Judee’s music and talked about the 10-year quest to make LOST ANGEL: The Genius of Judee Sill a reality. Brown and Lindstrom shared some amazing stories, including how they got access to a long-forgotten interview with Judee Sill from Chris Van Ness of the storied LA Free Press. (Hint: It involves an attic and some very old cassette tapes!) Read the full interview below.

The Interview with Lost Angel: The Genius of Judee Sill’s Andy Brown & Brian Lindstorm

[Editor’s note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.]

Ayla Ruby: I’m very excited to meet and to talk. Congratulations. This was just really well done, and it was haunting and beautiful and it was fantastic.

Andy Brown: Thank you.

Ayla Ruby: Can you talk about how this project came to be, how you both found Judee Sill? And I think I read that it started with seeing a YouTube video or introductions from other musicians?

Andy Brown: Yeah, I had first heard about her through Andy Partridge of XTC in an interview he did in 2000, and I kind of downloaded some bootlegs from Napster maybe. And then, when YouTube started, that The Old Grey Whistle Test video of her doing The Kiss appeared. And that slayed me and I showed it to Brian a year or so later. And then, Brian, do you want to pick it up from there?

Brian Lindstrom: I was finishing up a documentary, and literally, on my last day of the sound mix, my friend Michael Howell said, “You know who you should make a film about is Judee Sill.” And Andy and I started talking about the possibility of doing that, and we did a lot of detective work. First of all, we needed to make sure that no one else was already making that film, and luckily, no one was. And then, it kind of became this fun adventure of research, of trying to find the people who knew her. And we tracked all these people down in LA, and in December of 2013, we went down and did our first round of interviews.

Brian Lindstrom: And what really, I think, cemented, for us, the idea that we were on the right track about making a film about Judee is that all of her dear friends stressed how much fun she was. She wasn’t like a doom-and-gloom artist who you could tell was not going to have a happy life. She was actually a loving friend. She was kind of the life of the party in a really positive way, and they all just really clearly loved her. And not only did they have amazingly detailed memories of her, you could tell that she was still like a presence in their lives, that she really made a difference. And I think we thought, at that point, “If these people responded to you that way, maybe an audience will too.”

Andy Brown: Yeah. And in those days, there was a Wikipedia entry of Judee at that point that kind of described her as this sort of dark Nick Drake, female Nick Drake figure. And that was not the way her friends thought of her at all. So we felt, “Oh, this is important to show this other side of her as well.” But mostly, it was our love of her music and wanting to turn people onto it, I guess. And that would be true of everyone who participated in the film, I’d say, was spreading Judee’s music to a wider audience.

Ayla Ruby: There’s one person that you interviewed, and I can’t remember the name at the moment, who said, “Don’t let Judee’s music die.”

Andy Brown: Judee’s niece.

Ayla Ruby: Judee’s niece. And I feel like this documentary is the embodiment of that in so many ways.

Andy Brown: I hope so. Yeah, I do. I think, arguably, she’s more well-known now than she was in her lifetime, and that’s because of YouTube and Spotify and people can access that. But I think there’s a lot of good that Judee’s music can still do for people, and hopefully, will.

On reaching out to people to interview about Judee Sill for the documentary

Ayla Ruby: So you talked about going to LA, you talked for that first round of interviews. You talked about reaching out to her friends and anything. How does that come about? How did you identify these people? How did you convince them to talk to you? Because getting people to open up with stories is not always an easy task.

Brian Lindstrom: It isn’t an easy task, but I can only think of a few people who didn’t want to talk to us. And usually, it wasn’t really anything about Judee so much as it was maybe just being shy or something. But in general, people were just so excited that we were making the film, because they wanted so desperately for Judee’s music to reach people. And they felt like this is a chance for her in death to get what she never got in life, which is a wide audience and a kind of widespread appreciation of her incredible music.

Andy Brown: It’s also, I think, important to acknowledge the work that a fellow named Patrick Roques and Pat Thomas did when they issued her posthumous album, Dreams Come True, which was Judee and her musician friends recorded in ’75, when Judee was in a full cast or had just come out of a full body cast. There’s a great booklet that interviews a lot of the people that we interviewed, and that was our blueprint, that was our map to those people. So they laid the foundation for this whole film for us, almost 10 years before. We mentioned that, at the end, in the credits. But they did a lot of that initial work for us, so it helped a lot. It really did.

On what they learned about Judee Sill that surprised them

Ayla Ruby: That’s amazing. Is there a moment for each of you that sort of sticks out, that was surprising or unknown about her life, that you hadn’t realized maybe, based on everything you had known going into it, into the documentary?

Andy Brown: Mine would be that she told the truth about almost everything and that things that I thought might’ve been tall tales in her early life were all true. And to the point that, by the end of the film, this is not in the film, but she had mentioned, in the Rolling Stone interview, that her first husband, who she got an annulment from, had died going over the rapids in a rubber raft on LSD, the Kern River. And right at the end, we found newspaper clipping about… Clearly, it was that guy, it’s in the Rolling Stone interview of her, but we were not able to confirm this until the very end. I was like, “Yep. There’s another example of her telling the truth. She didn’t make this stuff up.”

Brian Lindstrom: The kind of amazing facts of Judee’s life, you read them and you think, “Well, perhaps this person’s a little bit self dramatizing or prone to exaggeration or self-promotion.” And that wasn’t the case. It all happened, and in all of our looks through her journals and papers and everything, we have never found a lie.

Ayla Ruby: That’s amazing. I don’t think that can be said for many people today.

Andy Brown: I think that was part of what her overall mission was though was to not be fake, to be real, to be honest, and to help… She wanted her music to help heal people, and it legitimized that mission by being honest about herself. It helped legitimize what she was trying to do musically.

Ayla Ruby: Well, there was all this talk about karma and leaving the world a better place with her music, and that seems to be kind of part of it too.

Andy Brown: Very much.

On the journey of getting source material for LOST ANGEL, including a lost cassette interview with the musician herself

Ayla Ruby: So you touched on the journals, and I have to ask about them, because they’re such a big part of the documentary. There’s our archival photographs, there’s the interviews, but this is told through her own words in many ways. I think I read that it was a long time before you got the journals, and I was hoping you could talk about that process and what it was like for you both when you finally got them.

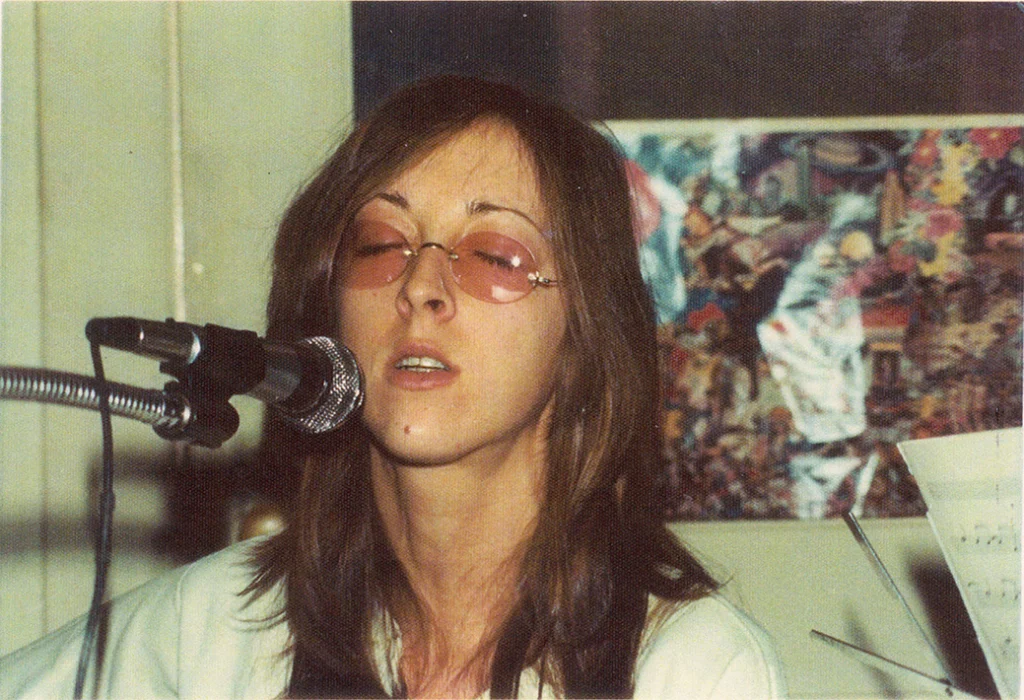

Andy Brown: It took about four or five years into… This film took 10 years to make, not that we were working nonstop for 10 years, but we treated it like we were writing a biography and we needed to get everything that was out there. We were aware of a box of Judee’s writings, that were in the possession of her cousin. We finally tracked that down and about, like I said, four or five years into the making of this, got that. And that allowed us to tell the story in Judee’s voice, at least the journals kind of start from ’73 to ’79. The first part is Judee telling her own story in her own voice, actually. Brian, do you want to tell how we ended getting that tape?

Brian Lindstrom: Sure. A great interview that Chris Van Ness of the LA Free Press did with Judee in 1972, and it’s just a comprehensive interview and pretty much covers her whole life. And we knew, wow, if we could have Judee saying the things in that interview on tape, it would be transformative. And we tracked down Chris Van Ness, who at that point had moved to Quinnipiac College in Connecticut. He was retired, but a very kindly secretary in the English department there said, “Wait a minute, Chris Van Ness, I think I know that name.” And she looked up and found an address, like a physical address.

Brian Lindstrom: And so, we wrote him and he was very kind and said, “Yes, I think I do have that tape in my attic. However, I’m wheelchair bound now and I literally can’t get up into the attic.” Luckily, Andy was in New York at that time, and so, Andy drove to Chris’s place, went up in the attic, and got the tape. And then, at that point, it was like, “Well, here’s a 50-year-old cassette tape, but is there even any audio information on it anymore? Is it all degraded and fallen apart?” Luckily, we had it transferred, and that moment when we first heard Judee’s voice, we knew that our film had gone to the next level that we…

Andy Brown: Oh, I remember how exciting that was. Oh my goodness, when we got that, and it was basically her telling the same story she was telling Grover Lewis that was in the Rolling Stone oral history. And then, it’s like, “Oh, great, we can do what we wanted to do, which is have Judee tell her own story.” The second, the journal stuff, is a voiceover actress reading Judee’s words, but the first stuff, most of all that first up to 1971, is in Judee’s voice, her own voice.

On going through Judee Sill’s journals

Ayla Ruby: Now, you talked about what it was like when you got that tape, when you were listening to it. And to bring it back to the journals a little bit, how did you go through them? What was it like for you reading them? Did you go through them together? What was that…

Andy Brown: Exhaustive, I’d say, multiple times going over and over things. Yes, we went through it together separately.

Brian Lindstrom: It was another eureka moment too, because we felt like, suddenly, we’re in Judee’s world. Just to hold something that she held, that she had written in, it just kind of really validated what we were up to.

Andy Brown: Yeah, it was a labor of love. It really was. Just having the opportunity to be able to make the film that we had hoped we could make, and getting this archive allowed us to do that.

Brian Lindstrom: And also, if I could be a little metaphysical, just to commune with Judee that deeply for that long, just really profound experience.

On how LOST ANGEL: The Genius of Judee Sill has impacted the filmmakers

Ayla Ruby: So you both sort of came into this with this idea of her. Do you feel like you’re leaving with the same idea, after holding these objects, after hearing her voice? Or how has the experience impacted you?

Brian Lindstrom: I think it’s really…

Andy Brown: Go ahead.

Brian Lindstrom: And confirmed all the things that we felt about her that led us to make the film, a fearlessness, a connection to something bigger than herself, a desire to make a difference, a feeling…

Andy Brown: Perseverance through suffering.

Brian Lindstrom: Yeah. But yeah, exactly, a feeling of truly examining pain, in order to perhaps transcend it and find some meaning in it.

Andy Brown: Very inspiring person, Judee, to me, personally. Yeah.

Ayla Ruby: Well, thank you. I really appreciate it.

Andy Brown: We appreciate it too. Thank you so much.

Ayla Ruby: It’s a beautiful documentary.

Brian Lindstrom: Thank you.

LOST ANGEL: The Genius of Judee Sill is now in playing limited theaters and available to watch on digital platforms.

Learn more about the documentary, including how to watch it on the big screen, at the Greenwich Entertainment website.