Not since 1999’s The Blair Witch Project has a horror campaign been quite as effective as the one Neon have instigated for Oswald Perkins’ horror Longlegs. The campaign that tore the internet apart at the turn of the millennium was based on the idea that the titular Blair Witch was a real entity and the film was actually a snuff piece being released in the cinema. The film went on to make hundreds of millions at the box office on a shoestring budget, making it one of the best return-of-investment movies ever. It also changed the marketing world as box office moguls realized how powerful the internet could be.

A viral marketing campaign with a mysterious phone number

Cut to 2024 and Neon have used the internet to virally market Longlegs as a must-see movie this summer, but did so without so much as a single image of the movie. Cryptic messages began being posted on social media, websites were created in the style of pre-fiber optic internet that showed disturbing crime scene photos, and a phone number was issued for people to call, with the eerie voice of Nicolas Cage’s eponymous serial killer character speaking back to them. As of July 13th, 2024, the film is now set to make upwards of $20 million at the US box office this weekend, making it Neon’s best box office weekend to date.

The film follows a “half-psychic” FBI agent in the early 1990’s named Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) and her involvement with the investigation into the 30-year mystery of Longlegs (Nicolas Cage), a serial killer whose mode of operations is to get a religiously inclined family man to murder his family and himself. But Longlegs doesn’t exist according to forensic evidence. There is nothing to suggest that he was ever anywhere near the home, bar a letter made up of cryptic symbols left at the scene, one that is scribed with the moniker Longlegs.

So with no evidence to work with, FBI agent Carter (Blair Underwood) conscripts Harker to the case. Soon, Harker – through a sense of supernatural intuition that can be described as a narrative cheat code – works out the link between the murders. She takes the date and plots them on a calendar, finding a pattern to who may be next on Longlegs’ murder agenda, while also tracing out a triangular symbol that appears to represent the devil.

Striking a delicate tone balance is notoriously difficult in film, and also highly subjective. The previously mentioned scene that follows Harker tracing dates on a calendar she wrote is presented as sinister; a pseudo-revelation of Longlegs affiliation with the occult. This can land like a damp squib if you’re not quite tuned in to its macabre, jet-black humor or enveloped in the darkness that the film seems to carefully curate. The same can be said about the Faustian bargain that makes up a decent enough twist near the end. It works to an extent but it fosters enough incredulity that you realise this narrative is built with so many flimsy elements that it could all come crashing down.

It doesn’t, though, through what seems like sheer willpower from Perkins. Longlegs is such a confident movie. The film oozes style, not in a way that might be attributed to a Guy Ritchie or Edgar Wright, but in how the form and texture are constantly brooding, slithering, and evolving with every chronological switch or perspective change. The film switches aspect ratios, frames its subjects slightly off-center, and fosters an indelible, evil, and disorientating atmosphere.

Longlegs the character is obscured early on

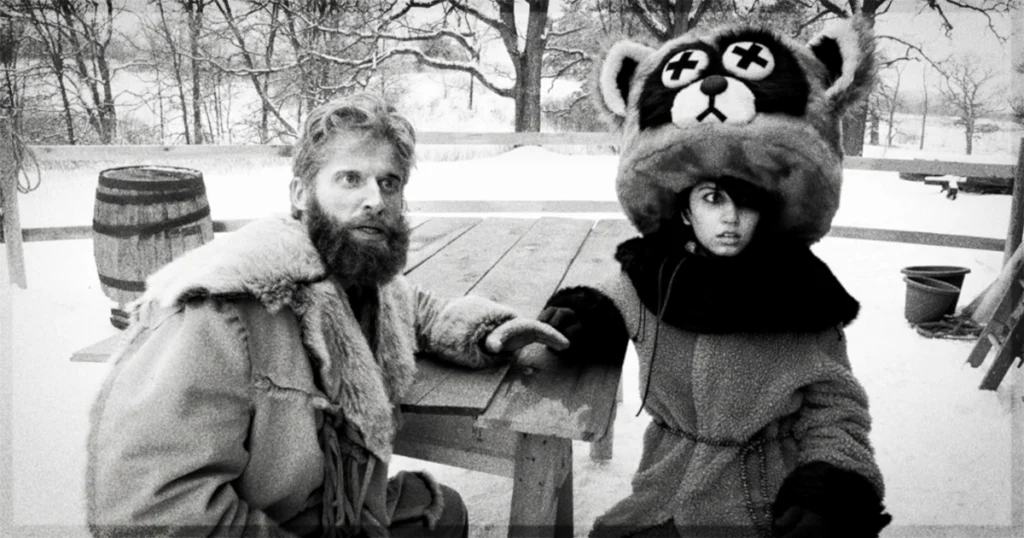

The marketing has kept the image of Nicolas Cage as Longlegs out of it’s marketing, so it’s surprising to see them invert the Jaws motif here: instead of keeping Longlegs a secret from the audience like the impending shark, the character is presented early on in the film but never in full view and never in full frame. Instead, they cut away a split second before his face can be processed by the naked eye, the image of Longlegs branded on eyeballs like the split-frame penis in Fight Club.

When we do get introduced to Longlegs, we see the disheveled, white-suited, unshorn antagonist listening to glam rock band T-Rex. This is not the sole reference to rock icons: the opening scene features a play card of lyrics from the T-Rex track ‘Get It On‘, and a Lou Reed ‘Transformer‘ poster is shown on his wall. Reed and Marc Bolan (vocalist for T-Rex) were unapologetically queer. They marketed themselves as such. Reed, known mostly for his songs’ Walk on the Wild Side‘ and ‘Satellite of Love‘.

Longlegs is a character that disturbs the status of the nuclear family; his victims are of a homogeneous variety, in that they are all religiously inclined, fearful of the devil and what is stereotypically discussed as ‘normal’. Perkins linking of queer glam rock icons with Longlegs is an element that hints and plays with the idea that queer repression is a trait of the devil. It’s no accident that the film is set in 1993, a time of great anxiety for queer folk while also being a time where satanic panic had infected morality of the hegemonic populous.

Longlegs and its stylistic predecessors

Longlegs is stylistically indebted to Jonathan Demme’s 1991 masterpiece The Silence of the Lambs, as my fellow critics have mentioned in abundance. But the film, to me, felt more akin to Bryan Fuller’s Hannibal TV show, where its main character Will Graham would find himself in situations similar to Maika Monroe’s protagonist Lee Harker. Graham, a character who was neurodivergent, assisted in cases through what is described as “pure empathy,” a trait that allowed him to see the crime from the killer’s perspective.

This is not quite as such with Longlegs, as Hannibal grounded itself in a sense of surreal realism. Instead, Longlegs is able to use Harker, a character who is played neurodivergent without a specific mention of it, whose supernatural abilities lead her to solve the mystery of Longlegs. Because the occult and supernaturality are invoked, there is a marked difference from every adaptation of the Hannibal Lecter story, even while taking visual references from them. Brian DePalma’s Carrie is also found ebbing at the seams of the picture; Harker is an almost Carrie-like enigma, if the titular character had grown up, as she also plays a victim of parental and religious restraint. Take note of a cracker of a supporting performance from Alicia Witt as the zealous mother of Harker.

But while I find musing on neurodiverse characters being played straight an enticing sort, there is an oddness that one must recognize. Harker is no doubt played as autistic. Her clipped dialogue, and the tiny ticks that occur alongside her inability to hold eye contact are common traits. Longlegs implies that the devil is responsible for her behavior, and it’s a slippery slope to then run with that and read the text of the film as the devil being a cause for autism. I don’t believe this was the intention, but through various revelations and textual ideas, it somehow purports this.

What the marketing does not prepare you for, no matter how many pull quotes it uses about it being “terrifying,” is just how truly disturbing the film is on a subdermal level. The deep background of wide shots contains mysterious flickers like a Rorschach test swirling with hidden demons, while the ear-splitting soundscape hums and screeches underneath this discombobulating, deeply unsettling horror. It is less under your skin as it is rooted in the nucleus of your cells.

Longlegs is a film that never lets up. Even when having to blindly wade through it’s sludge of slow-burn plot to get to the clumsily, freakishly situated nugget of exposition that seems to gloriously explode onto the scene, arriving to both demystify the character of Longlegs and add another delicious layer to this medley of poisonous scares.

Final thoughts on this Oz Perkins film

Good horror thrills briefly; great horror you’ll find festering in your nostrils like the acrid smell of maggots entering rotting flesh long after you’ve turned the lights on. Longlegs is that kind of horror, even if Perkins’ house of cards comes crashing down on scrutiny. An acid-coated procedural, where real fear emerges not solely from Nicolas Cages’ eccentric Marc Bolan-esque serial killer or from the crisp, violent screeches of Zilgi’s score but in the echoey sparseness of sound in Perkins’ wide images that languish with a sense of skin-peeling dread and in the idea that the devil is in the details. Literally.

Longlegs is now in theaters.

Learn more about the film, including how to buy tickets, at the official website.