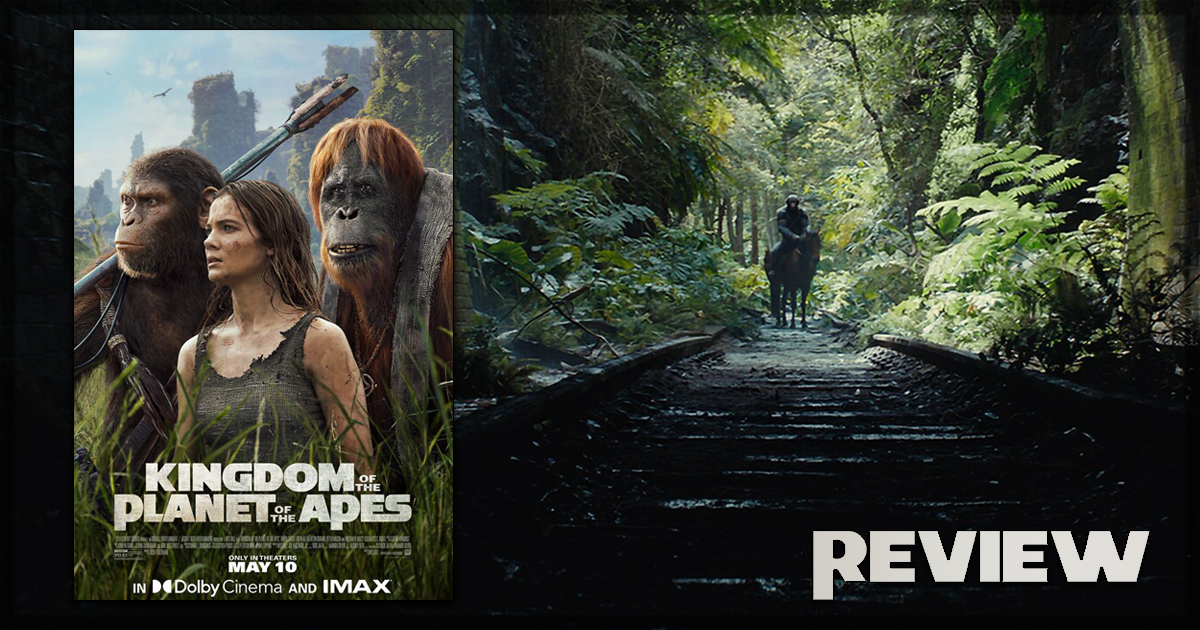

Mark Twain once said that, “History does not repeat itself. It rhymes.” The Planet of the Apes series, now on its tenth installment, embodies this. The original 1968 Charlton Heston vehicle ended with his character Taylor in a state of despair at realizing the world of ‘damn dirty apes’ that he crash-landed on was the very Earth he had left 2010 years prior. The iconic final image is of the Statue of Liberty, once revered as a symbol of hope to immigrants, lying submerged in sand, a visual carcass of a once all-powerful kingdom. In Wes Ball’s Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, the symbols of the American kingdom that once dominated the planet loom loud as ever-present monuments to a past lost. The rhyme of the franchise is that within its rebooted form, the existence of its prior entries are those monuments, a skeletal structure for the franchise to build upon and find new, exciting ways to parable the world that exists outside a cinema screen.

[Editor’s note: There are spoilers ahead for Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes.]

The Evolution of a Franchise

Many generations have passed since 2017’s War for the Planet of the Apes. The Matt Reeves-directed epic that took Caesar (Andy Serkis), notably named for the infamous Roman general, on a mission to rescue his people set the stage for biblical connotations with Caesar’s death at the end. The death occurs after taking his people outside of human civilization onto a promised land. War presented him as a supplant for a religious savior, a Jesus-Moses hybrid where he leads his people to freedom and sacrifices himself in the process. Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes takes on the task of showing how the message of one revered as a deity, one with wholly good intentions, can be corrupted in a world of hearsay and unreliable communication methods.

In Kingdom, the words of Caesar – “Apes. Together. Strong” – has been perverted by an ape, Proximus Caesar (Kevin Durand). This ape, who has taken the name of Caesar to invoke the power of their ‘creator,’ has become a tyrannical dictator with the skewered desire to evolve, no matter how many apes he must sacrifice along the way or how many ape villages he must destroy. One such village is that of Noa’s (Owen Teague), a quiet settlement that rears eagles and smokes fish but one that is content with their settlement not impacting the larger world.

The elder apes of Noa’s village refer to humankind, now completely feral and mute after the virus mutated at the end of War, as “echoes.” What is fascinating about the village using the word echo is that they don’t understand it. They can’t. The word, and language as a whole, has been passed down generation to generation. It is a word that, in context, is loaded with scientific connotations surrounding evolution, and yet, they know not of it, but they still declare the humans as echoes, like there is a subliminal knowledge of world history that they otherwise refuse to engage with.

After the destruction of the village and kidnapping of his people, Noa mounts his horse and begins the quest to find the villagers taken by Proximus Ceasar’s militant gorilla contingent to a shoreline internment camp that a keen eye might recognize as the beach from the 1968 film. Along the way is where Ball and scriptwriter Josh Friedman begin to discuss the ramifications of societal degradation amidst deification and communication breakdown. Noa, an ape who has taken the word of his elders as fact, finds a version of a new truth along his journey.

Proximus Caesar and Raka: Two Sides of the Same Deified Coin

He meets Raka (Peter Macon), an intelligent, well-spoken orangutan who carries books along like they are bibles. He cannot read them, but through blind faith in the teachings of Caesar he knows of their importance. Raka believes these contain the key to unifying apes and humans. But what becomes apparent quite quickly within Raka’s binary view on humankind is that it is the same as Proximus Caesar’s, only inverted. Raka’s truth, which we know from previous entries in the series, is mostly factual and has amendments; it has been manipulated by the whispers and fragments of conversation that occurred over the previous centuries.

Raka and Proximus Ceasar are two sides of the same coin. Raka deals with the mythological idea of Caesar, wearing the symbol of the ape – that of the window Caesar looks out of in Rise – around his neck like a monk’s trinket. Proximus Caesar deals with an absolute in a way that is adjacent to the science once discovered by humans.

His goal to get into a secured vault stems from the notion that what is inside will instantly evolve him and his people further than natural evolution would occur. It’s overly-simplistic, carnal thinking that has occurred since because Proximus has been read second-hand Roman history from a human (William H. Macy), alone who maintains their cognition. Without books and writing on ape history, it then falls to Chinese whispers to keep historical fact alive, along with unsound ideas of science. It seems then that the generations between Caesar’s death and the time of Kingdom has been The Dark Ages, a portion of history lost to the destruction of the written word.

The Visual Landscape: Beauty and Familiarity in a Digital World

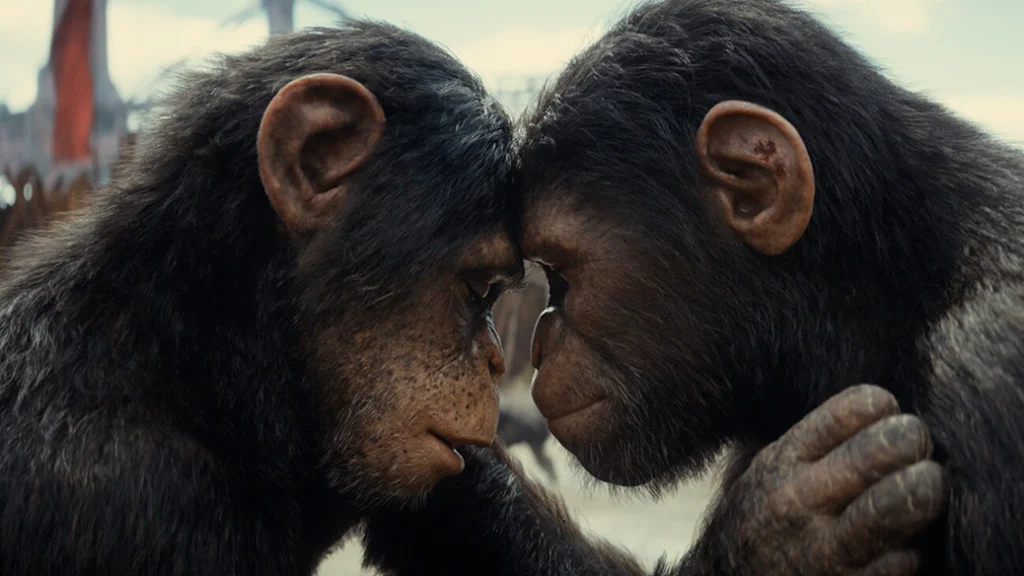

This makes the inner thematic workings of the vast world re-built by Ball and Friedman so fascinating. It’s a slight shame that, in unfair comparison to the previous Reeves-directed entries, it lacks the visual splendor. Everything is competent on the visual front, with WETA Digital’s effects continuing their phenomenal work with motion capture, but there’s a tangible magic to the filmmaking that is not quite here. Perhaps my revisiting of the original quintet of films, where the apes were performed in physical costume rather than in motion capture, has clouded my outlook, but there’s something too clean and shiny about the whole digital experience here.

That being said, Durand’s performance as Proximus specifically finds his exuberant physicality captured with resounding vigor, but even if the character is a wide-eyed maniac, Proximus is too ineffective a presence. Teague’s Noa is also a character that is more interesting on paper than the performance given, as is the human character that Raka names Nova (Freya Allan). This is the first entry in the franchise under the umbrella of Disney production, and while everything is perfectly fine, it also doesn’t feel like it’s risking anything. This can be summed up in the supposed death of a character, where there is too little impact to it. As an audience, we have been conditioned by Disney’s output to correlate this visual timidity with a lack of impact around death. Disney’s poor relationship with characters remaining dead has sadly impacted a film not within the scope of the superhero genre.

Biblical Echoes in a Simian World: Symbolism and Themes in Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes

It’s no accident that our new protagonist, Noa, is only a single H away from being another biblical figure. The righteous Noah, a character within Christianity that was beloved by God, paved the way for sin to be washed away from Earth by rescuing the creatures of the planet on an Ark. Noa’s journey continues the biblical inferences within the franchise that first began in 1968, with the governmental rulers of that world also acting under a theocracy. This can also be seen through Kingdom’s presentation of the pharisaic Proximus Caesar, whose hyperreligiosity reverberates backward through the franchise as a rhyme to impact that of Taylor (whom we subtly witness depart Earth in 2011’s reboot Rise).

It is obvious that Ball has an affection for the franchise with Kingdom through the many textual rhymes and references to it. While the theological ideas placed intermittently in the unhurried film are ravishing to digest, they are slightly insubstantial in comparison to the allegories of prior entries. However, should the next installment in this supposed new trilogy be helmed by Ball or someone with as much passion in keeping those rhymes, it is in safe enough hands shall they be allowed to take the big swings and strive for more than the generic action blockbuster that Kingdom often dips into.