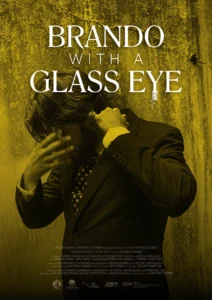

Brando with a Glass Eye, from filmmaker Antonis Tsonis, recently premiered at the Slamdance International Film Festival in Utah. In 2023, indie movies such as Past Lives, All of Us Strangers, and Anatomy of a Fall enthralled everyone with their superb storytelling that first had the world’s eyes on them at film festivals. All these films went from one festival to another, gathering up awards and fans. Slamdance is one of those special festivals that helps get indie filmmakers noticed. It’s proven crucial for debut filmmakers, with famous alums like the Russo brothers. In an exclusive in-depth interview, we talked to Antonis Tsonis and Tia Spanos Tsonis about Brando with a Glass Eye.

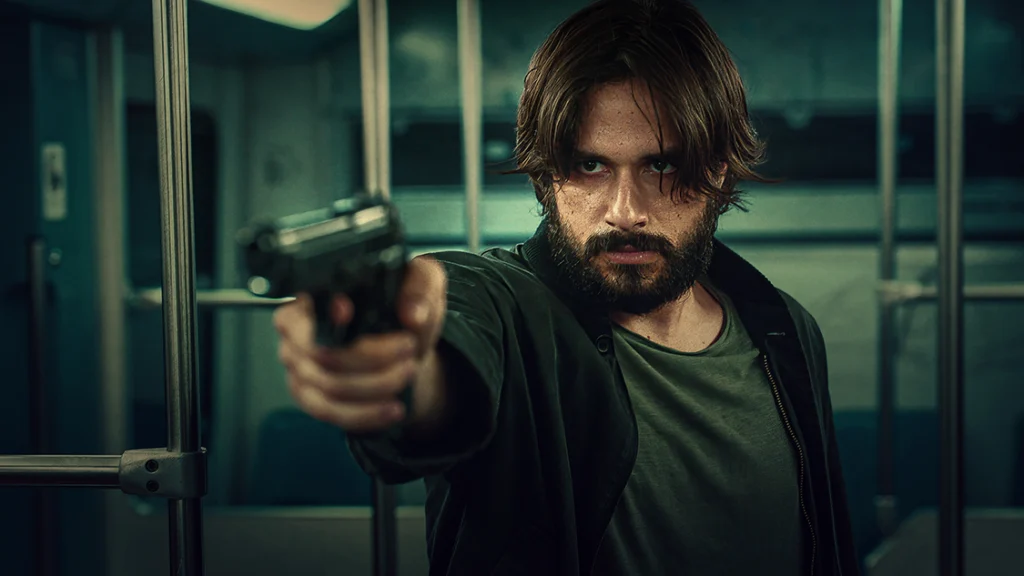

It is a Greek movie that chronicles the journey of an aspiring actor named Luca (Yiannis Niarros). However, things go downhill when he accidentally hurts someone during a failed heist. A compelling yet dark story follows about method acting going to the extreme, with the line blurred, real, and fictional. Brando with a Glass Eye is a very unorthodox take on method acting with some very daring filmmaking by Tsonis.

Aayush Sharma talked with director Antonis Tsonis and producer Tia Spanos Tsonis over Zoom to learn about what went behind the scenes and their journey to filmmaking. They shared what it was like working with Yiannos Niarros and how they managed to make Luca, a character who does such morally wrong things so rootworthy and so sympathetic.

The Interview with director Antonis Tsonis and producer Tia Spanos Tsonis

[Editor’s note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.]

Aayush Sharma: So first of all, I would like to welcome you guys. Thank you so much for joining me and talking about this movie. So I would just start by congratulating you for this amazing movie. I was thoroughly engrossed when I watched the movie. I would just like to start with Antonis. So I was going through your IMDB page. I found out that Brando with a Glass Eye is your first feature length film. Prior to this, you have worked on various shorts. So how was the transition likes from shorts to a feature length film?

Antonis Tsonis: Before I answer the question, thank you so much for watching the film and for your kind words. I really appreciate they’re very important to people at my stage of development and they’re very encouraging and they make a big difference to our daily lives as filmmakers. So I thank you for that. To answer your question, the transition, it’s quite a significant transition, in fact, because you have to do everything on a bigger scale. And in terms of the relationships you build, they become very powerful because they’re over a longer period of time.

Antonis Tsonis: And the type of film that we’re engaging in does require us to try to strike to a high level of authenticity, which means I believe, at least in my style of direction, I like to work with people that I genuinely have a common goal to achieve a common aesthetic and then to get under each other’s, other’s skin, if you will, get to know each other on a very intimate level. And I believe that when you do that, that can hopefully translate into the film and be preserved in the picture of the film as kind of the aura of the film, if you will. So the hardest thing was giving the aura across two hours as opposed to 20 minutes. That was the hardest thing. But then what happened, it became natural. I forgot about all that and just concentrated on making the story.

Brando with a Glass Eye’s Antonis Tsonis did not always want to be a filmmaker

Aayush Sharma: Just getting into this movie, I also wanted to know about your work in the past. So do you always wanted to be a filmmaker or this happened as the time passed?

Antonis Tsonis: Ah, that’s a very good question. I started writing poetry for some reason very young, and I kept doing that. That writing evolved into doing really well in English at school. And that was a subject that I noticed I was just natural. In mathematics I would get good marks, but I had to work harder than some of the other naturally inclined mathematical minds and peers and friends of mine.

Antonis Tsonis: But when he came to English, there was something about it that I loved and it was very natural to me and didn’t feel like work. And storytelling was a big thing in my life from very young. And then what happened is I went down the academic path and did a law degree, which it was kind of like I really didn’t know what to do with my life at that point. I’d gone through an illness in year 12, which year 12 is the last year of high school. It was a very serious illness and it went for about three, four years, but no one could diagnose the illness.

Antonis Tsonis: So I just put in law school because I thought just put in something. And it was more to show myself that I’d conquered surviving high school, let alone because of the illness which was cured thankfully. And from there I went to law school and I was a natural at law school. I didn’t really have to worry too much. I went to the classes and things and whatnot. But then I discovered the philosophy of law, which is jurisprudence, and I fell in love with this. That led me to a doctorate and I wanted to be a writer.

Antonis Tsonis: I never lost focus of being a writer. I wanted to engage at that level of education in order to be able to write as a continental international writer and be aware of different philosophies from the continent, being France and existentialism and platonic thoughts and Aristotle and all these things, and a lot of other philosophies that you engage in order to do a doctorate in law.

Viewing Bicycle Thieves by De Sica changed the course of Tsonis’ life

Antonis Tsonis: So mine was very theoretically based. And during that period, of course, as I was studying, I discovered Italian neo-realist cinemas. Specifically, I watched a film called the Bicycle Thieves (Ladri di biciclette) that you’re probably aware of by De Sica. And I fell in love and I said, this is what I want to do. I want to give something to humanity. I want my life to not be a lecturer at a university or a lawyer, which is great for those people that do what, I’m not putting that down.

Antonis Tsonis: But that film struck a chord with me and literally changed my life, that film. And from there I discovered other Italian cinema and I discovered Fellini and Kubrick, and then I went into the American independent cinema. So as I was studying philosophy, I was watching brilliant films. Then I started to make films with no money at all, like little shorts, experimentals, and getting little nominations even for acting in little festivals here and there. Just anything I could get my hands on, any camera, anything I could do.

Before Brando with a Glass Eye, there was the film 3000

Antonis Tsonis: And those little exposures and little sort of successes here and there led to the more substantive short films that I did, which was the Firebird, which won best short film in Manhattan in New York, which I was very proud of at the time and still am. And then I did 3000, which I went back home. I was born in Athens, the motherland, if you will. I was born in Athens. However, my parents migrated to Australia when I was only a baby. So for intents and purposes, I’m second generation, but we always maintained a good connection, a strong connection to Athens.

Antonis Tsonis: And I went back and did a short film called 3000. And it was a funny story that one, because I had to give up another story set in 1938, another short film in Berlin, and there was some complications with the production there. So I thought, it’s not safe to go there. So I pulled out of that with my cinematographer, who’s from Berlin, and we went to Athens. I said, “I want to go somewhere else.” I said, “Would you come to another city?” He goes, “I’ll come anywhere in the world for you, Antonis,” because we’re very close, my cinematographer.

Antonis Tsonis: I said, “Let’s go to Athens. These are the two scripts.” And we chose 3000. And this is the interesting part, with 3000, I thought to myself, okay, say goodbye to the American independent film circuit, which I love. Say goodbye because this is a Greek language film. I had a limited sort of perspective on things, so I wasn’t exposed enough. And then lo and behold, we did 3000 and did extremely well in the independent short film circuit, in particular in the south, in southern America, southern USA, I should say.

Tsonis and co. gravitated towards Brando with a Glass Eye as his debut feature

Antonis Tsonis: So that was a eyeopener. And then I thought to myself, because all my work, I wanted to be in English, and it will be in English, but I thought to myself, I’ve made these wonderful connections and wonderful friendships making 3000. And I had a script with me when I went to a Berlin seminar. I had three scripts, actually. One set in Melbourne, one set on a Greek island, and another one set in Athens, Brando with a Glass Eye.

Antonis Tsonis: And everybody was sort of gravitating towards Brando with a Glass Eye. And because of the experience with 3000, I said, you know what? I’ll go back to Athens to do my debut feature. I thought it was a really nice thing to do to sort of do something in your mother language, which that was very challenging because English is my first language. That was very challenging, and we can talk about that too, but that’s why I went back to Athens.

Antonis Tsonis: It was in the back of the short film and the wonderful relationships I made. And also the story Brando with a Glass Eye, it could be a story that you could sort of shoot anywhere in particular, in countries where there’s a bigger distance, if you will, between the USA and the given country. So Athens was a very good pick for the story as well, because it is about a young method actor who really is occupying or creating or living inside of his head in a different world.

Antonis Tsonis: And the lens of Athens for him is very different to a more sort of standard perspective of a Greek character moving through Athens. This is a very unique character in the sense that he’s bringing American culture and Italian cinema and French poetic realism into his world. It’s integrated into his body, into his being, and he’s moving through Athens. And he appears to be even crazy to himself in moments, but he’s actually not. But he does go to the edge, as you saw in the film. Yeah.

On what happens behind the scenes of Brando with a Glass Eye

Aayush Sharma: Just like you said about the story about Brando with a Glass Eye, this is a very unorthodox take on someone who wants to be an actor. Big banners mostly don’t go to this length to get a story as such. What happened behind the scenes while writing and producing such a fascinating and a dark story? So this question is for you both. You both can answer this.

Antonis Tsonis: Yeah, I’ll let Tia go first.

Tia Spanos Tsonis: I was going to let Antonis. What happened behind the scenes? Well, I think that Antonis presented me with a title first. We were just driving to work one day and he’s like, “I have this title in my head, Brando with a Glass Eye,” and it pricked my ear. And I thought, “Okay, what are you thinking?” And he said, it’s a story. And he just sort of gave me a few little words that I pieced together and I said, “I really love this idea.”

Tia Spanos Tsonis: So I encouraged Antonis to take 10 days away from everything, and I said, “If Rocky could do it, if Sylvester Stallone could do it for Rocky, you’re going to do this for Brando with a Glass Eye. I want you to forget about the world for 10 days, and I want you to write me a script in 10 days.” So he went into a lockdown. This is pre-COVID. Actually, no, it was just before COVID. And sure enough, then he presented me with maybe a hundred pages after 10 days.

Tia Spanos Tsonis: I read the story and I said, “okay, great. This is a fantastic foundation. Congratulations, Antonis.” Of course, it’s not the script that we ended up with, but that was how it all started. So we had a very American independent film culture in our mind and in our heart going out there and sort of saying, okay, you’ve got 10 days, write a script. And then of course, the natural progression of pitching it, finding the right co-producers, finding the right production services team in Athens.

A strong support system including Maria Drandaki and Blake Northfield helped Brando with a Glass Eye

Tia Spanos Tsonis: We have the most incredible support around us, and that’s so important for first time feature filmmakers. And of course, this was my first feature film as a lead producer so my team was everything. And so Maria Drandaki, who is a very seasoned producer in Athens from Homemade Films, she’s our executive producer. But she also provided the production services for the crew and everything on the ground in Athens. And my amazing co-producer, Blake Northfield from Bronte Pictures in Australia who assisted us after we got everything in the can and facilitated through The Post Lounge, the post-production part of the film.

Tia Spanos Tsonis: So it was a story that I wanted to say as a producer, and I think that’s really important for anybody out there. It’s important to make films that you feel you want to share with the world. And it is a dark story, and there’s a lot of sentiment in it, and there’s a lot of layers. I refer to it as a Greek babushka doll. You see it once and then you might see it again and you might see it again. But even if you only see it once, there are so many things to process.

Tia Spanos Tsonis: I think the pictures in place. Where you may miss the subtitle or not listen to the dialogue, the picture will say the story for you as well. You get lost and immersed in a world which is contemporary Athens, but with this beautiful throwback to Italian cinema and independent cinema of the seventies in America. And I love that. I love that.

The theme of beauty under the veil of darkness plays heavily in the movie

Antonis Tsonis: Yeah. I can also say something about the dark part. That’s a really good question. Yeah, I think one of the I guess sub themes or one of the drivers I guess in the writing too, is an idea that I’ve been playing with and that I believe in. I mean, what is beauty? And sometimes the beautiful, or often actually, the beautiful can be discovered in places that we don’t expect it to be. So the darkness is sort of like a veil, if you will, to something that sits under it that is beautiful in my eyes at least.

So for me, Luca is a beautiful character. He does a bad thing, of course. I did a lot of research. I spoke to even method actors and they couldn’t give me the names of course, and I didn’t ask. But there are many students who’ve never made it and others who have made it, in the conventional sense of the word having made it, that have done some things that aren’t very good in order to get ahead in their dream to raise the funds and things like this.

Antonis Tsonis: So there’s an underlying realism to it. But as I said before, I’m very influenced by the French poetic realism. Although I became a filmmaker because of the Italian realism, my work actually just naturally goes towards the poetic realism, which is basically constructing a realism, but then making it poetic. And the darkness for me has a certain quality of poetry, and there’s a resistance happening between the darkness and the emergence of a beauty.

In Brando with a Glass Eye, Luca helps drive the human message of being careful when judging ourselves and others

Antonis Tsonis: And Luca comes to terms with this in his own subtle ways. In the scene where he defines beauty to his brother, he says, be careful what you call ugly in the third principle of beauty that he makes up. So this is kind of like the message too. We have to, as human beings, be careful of what we see in the mirror when we look at ourselves. We have to be careful of judgements we throw at ourselves or at our friends or loved ones or strangers even.

Antonis Tsonis: And sometimes where we think we see there is beauty, there might be something very sinister and bad. And sometimes where we think that there’s something that’s not beautiful, it might be very beautiful, and the struggle to become beautiful is also another sub theme. So Luca struggles through his own darkness. And the craft of method acting too, the craft itself is a process towards beauty that often requires dark explorations. That have sometimes very sinister and negative effects on actors. This film in no way condones that.

Antonis Tsonis: I think that the train scene captures this very well in that what he could have become, he was on the brink of actually crossing the line and blurring reality and performance to the point that it’s dangerous and to the point that there’s nothing between it. Where’s the line? But then there’s something subtle in the film early on where he says the monologue about him to the girl that’s in the coma, and in the train scene, she opens her eyes.

Antonis Tsonis: So that’s my way of saying that method acting and life itself and our actions are a power over life and death. That’s how powerful we all are, and we’ve got to be careful in our actions. So he says this sort of monologue to the girl who’s in the coma when he’s hiding in her room, and she hears it somehow, in my mind at least subconsciously. At the moment that he was going to commit the mass murder, her eyes open. So he will never know, Luca, that he saved the life.

Antonis Tsonis: And later on Ilias (Alexandros Chrysanthopoulos), who he generally becomes one soul in two bodies generally becomes the Aristotle definition of friendship. He dies, but Luca never knows. That’s the hidden tragedy in the film for me. He never knows that he saved a young, beautiful girl, saved her. She woke up because of his story, and it’s because of method acting actually. So it’s a strange thing in the film. There’s that as well. Yeah. So that’s how I treated the dark side.

On how you make Luca sympathetic after his dark deeds

Aayush Sharma: So I actually wanted to follow up that question. Just like you mentioned, even though the central character has done something bad in the movie, and we as viewers feel, we empathize with him even after doing a crime or hurting someone.

Antonis Tsonis: Yes, we do.

Aayush Sharma: So how and where do you draw the line so that the viewer won’t just hate the central character?

Antonis Tsonis: Yeah, it’s hard. Look, the truth is, and this is one thing I’m happy about, when I read or say what the film’s about, I think to myself, I default into direction mode. How’s that going to work? How is that going to work? And then I think of the film that we’ve shot and it does work. As you’re saying, we pulled that off, so to speak, and I’m really proud of that aspect that you’ve drawn out.

Antonis Tsonis: The thing is, I think we feel sympathy for him, even though he’s committed the heist, because I think at the end of the day, we know he didn’t intend to hurt someone. And that’s no excuse to the botched heist. But we know that the film doesn’t start with him… It starts with him saying, take a paper gun and walk around for it, see how it makes you feel. It’s a method acting exercise, but that’s a dangerous exercise.

Antonis Tsonis: Popular culture understands that method, acting can be dangerous if it’s unchecked. And this straight away from the very first frame of the film, from the very first, when he breaks the fourth wall and looks into the camera, he’s basically saying, I’m only going to deal with a paper gun. But really the character itself actually ends up using a real gun, and that’s not part of his acting. That’s the getting to method acting back in New York to raise the money.

Antonis Tsonis: But at the end of the day, I think we empathize and sympathize for him, or rather probably sympathize, not empathize. We sympathize with him because we know that he didn’t intend to hurt anyone. I think that’s what it’s, and also we build his world very quickly. We show him walking through the meat market. We show him doing some crazy things, but then the brother talks to him while he’s sleeping. He’s painted his eyes. All these things, I think they build up. He’s watching the TV, he’s smoking the joint, with his brother in the room. And also we worked a lot with Yiannis to deliver the character in a sympathetic way as well.

Antonis Tsonis: And the camera angles do help.

On Stella Adler as Luca’s television muse in Brando with a Glass Eye

Aayush Sharma: Yeah, I really love the scene when he’s watching the TV and the lady in that knows what to think from that instance. She’s actually talking, but just not talking about acting. She’s also talking about life, how life works through all the…

Antonis Tsonis: Correct. Yeah. That’s very good. Yeah, that’s a very important part of the film. So as Stella Adler is talking to him, and from the TV from the past, from the grave, so to speak, but her wisdom is time immemorial. And although she’s scolding him and sort of giving a hard time, if you will, that’s what Stella Adler was known for. But her toughness, her toughness was the pathway to greatness for people like Marlon Brando and James Dean and Mark Ruffalo and the list goes on, and De Niro, in fact. So it’s whoever taught these guys hands on. And one of her favorite students, if not her favorite student, was indeed Marlon Brando. So having Luca, that’s what Luca plays on the TV, old video recording. He plays it over and over. He lives around her. She’s his mentor, his muse, his inspiration.

Antonis Tsonis: But what I like about the film, what it delivers, and you picked up on that, she’s not telling him how to act, but she’s telling him how to live as an actor. She’s telling him how to be. As a human, have something to say, have something to say. She says, “We in America have nothing to say.” And she’s tough in that scene where he wrecks the mother’s bedroom. She’s really tough on him. I mean, it’s really tough on the character I should say. Obviously, it’s playing on the TV and Stella Adler never meets Luca, but it’s tough on him as a character because the actor hasn’t changed. The actor hasn’t changed. It’s the same thing.

Antonis Tsonis: And we talked about darkness before. Maybe some would see Stella’s method is a little bit dark in that sense of the toughness, but it was her way of showing the actor how to find a soul in order to have something to say, in order to act, in order to be beautiful in their performances, regardless of what they’re playing. So this was very important in the film, the idea that the birth of an actor is the birth of a soul in the context of wanting to be an actor.

On working with Yiannis Niarros

Aayush Sharma: So you guys are working with such a stellar cast. Everyone has worked superbly, especially Yiannis Niarros. Was the role particularly written for him, or there was this strenuous audition procedure that you guys went through?

Antonis Tsonis: Another great question. I met Yiannis at the LA Greek Film Festival. It was one of the festivals that 3000 played in. I approached him and he approached me and we liked each other a lot. And what happened is I asked him, I said, “Would you ever play in a film?” And he loved 3000. Actually, that’s the best way to meet someone actually at a film festival. They watch your film and they come and speak to you so they know something about you because they’ve seen the film.

Antonis Tsonis: So he came up. He went with a group of other actors, which I was very honored by this. He was there for a feature and they took the time to come and see the short film. Then he came up to me, actually. That’s what happened and we got talking and we really liked each other. And I asked him, after a few days, we getting to know each other, I asked him, “Would you ever consider doing a feature with me?” He said yes.

Antonis Tsonis: So when the idea came up independently of Yiannis, because I knew another actor who unfortunately passed away, who played in 3000, and he was close with me as well. So always going to be between Yiannis and Panos [Natsis] was the name of the other actor. Yiannis got the role before Panos passed, which is nice in the sense for Yianni. I didn’t choose Yianni only because I lost Panos, but I didn’t actually get the chance to tell Panos that Yiannis got the role. He wouldn’t have minded it because he was a great friend and there would be other opportunities for him had he not passed.

Antonis Tsonis: So that was a hard period for us. We lost the actor from our short film that we truly loved. He went on to become very, very famous in Athens through some of the shows that he did because he was doing a lot of TV shows, which that’s how they make their bread and butter, the actors in Greece.

On translating Yiannis Niarros’ theater strengths to film

Antonis Tsonis: Yiannis is a sublime theater actor and we played on that. Instead of going back to this thing about the darkness, the way the brother eats the tomato sandwich. All these things, the grotesque of cinema, sorry, of theater, we used some of that in the way we constructed the character, but also the way we framed the character. You talked about the sympathy aspect. We stayed close on Luca often, showing his face, and we worked on subtle performances.

Antonis Tsonis: We wanted to hit something that was highly emotional but not melodramatic. That was one of my key things from a directional point of view. So if I saw something that was slipping, not that Yianni is a melodramatic actor, but if I saw anything of the sort slipping that way, I would call another take. I would never tell Yianni what it was that I was seeing. I would never tell, which would’ve been hard for him. A lot of directors give a lot of feedback, a lot don’t. I tend to not. It’s more cinematic and more just general strokes, general suggestions, because otherwise the actor will become overwhelmed by the direction.

Antonis Tsonis: Yianni’s a competent actor, he doesn’t need to be over directed in that sense. What we did is we found our rhythm together. And it was interesting seeing the theater actor who knows of cinema doing playing this highly cinematic role. That was a really cool part of this because I respect the cinema, sorry, the theater, as much as I respect the cinema. Yeah, so that’s that.

On how Tia Spanos Tsonis balances artistic vision and commercial viability

Aayush Sharma: Amazing. Tia, next question is for you, because as a producer you have to think a lot. You have to think about a lot of things. But I think one of the most important aspects is to navigate the balance between artistic vision and commercial viability. So how did you do that?

Tia Spanos Tsonis: Yes, that’s a very good question. Very good perception. Well, there is a fine line between the creative producer and of course the producer that has to know that they’re going to sell a film. And there are a lot of things that I had to keep in mind; things like running time, things like parts of storylines that had to be cut out of the film with the director. We had a four-hour assembly and landed with a two-hour film. It was 117 minutes, and then the five minutes of rolling credits just for the music to set in.

Tia Spanos Tsonis: It’s all about balancing time, time management, managing the director through that post-production process, and also knowing what to do next time. And as a producer, once you’ve done one, and of course as you get stronger and you do more and more producing, you see the red flag. You can spot the red flags sooner as experience comes. So there will be things that I will be able to do in the future that I wasn’t even aware of doing in Brando. For example, I may have been a little bit stricter on how many scenes we shoot or condensing the script a little bit, but you’re always up against time and money. So I always have to say, well, we’re balancing time, money, and artistic vision.

Tia Spanos Tsonis: And there are times where the producer will win, and there are many times that the director will win. And I think it’s about balancing the relationships with the director and the type of director you are working with. Antonis is very auteur, so sometimes you have to surrender a little bit to the Eurocentric vibe of Antonis. And then I have to say, okay, well that’s going to work or that’s not going to work. But I have a super team around me and I did turn to my beautiful council of other producers, my executive producers and my co-producers and flag or question or ask them questions, and that was amazing. So yeah, it’s a balancing act. It is a beautiful balancing act.

On what Slamdance means for filmmakers and Brando with a Glass Eye

Aayush Sharma: I just want to end this interview on a very lighter note. I just want to ask, you guys are now promoting this movie all around the US, and all around the world at the Slamdance film festival. How important it is for you guys when such a large audience will see the movie in a big theater and people will be talking to you? So how important and how significant is this moment for you guys?

Antonis Tsonis: I think that it’s a very, very, very, very, very important moment, and I very much look forward to seeing it tonight. We’re playing at 9:40 and we’re playing again on Wednesday. But tonight’s special, as Wednesday will be, there’s Q&As at the end, which I really looking forward to doing the Q&A’s in an audience environment. Of course, I’m supporting the other films here and seeing how that’s going for them, and they’ve all done so well. And it’s such a wonderful thing to be here at this festival.

Antonis Tsonis: It’s a very humble festival. It’s a really, really energetic and very authentic people. I don’t know how they do it at Slamdance, but the 10 narrative features, competition that we’re in, they’re all very humble and authentic people, at least what I’ve seen. It’s very important because the international exposure and getting people to talk about it and to write about it, it’s huge. For us it’s life changing because we have many stories we want to tell. We have our next stories lined up and everything hinges on your next move.

Antonis Tsonis: There’s so much at risk always when you make a film. And if you think about the risk, you’ll never make a film. So I guess you have to go out there and surrender to the process of making the film, as opposed to trying to sort of strategize and preempt everything that can go wrong. You have to go in there and ignore everything that can go wrong and make sure, and give all your effort and might to make sure you do everything in your power and in your ability to ensure that the least amount of things can go wrong.

Tia Spanos Tsonis: I think it’s an incredible platform for filmmakers. In fact, Slamdance is the most important stage for the independent filmmaker around the world. And the beautiful thing about Slamdance and what we have discovered in the narrative features category is that we are all first time, well, it’s all first time debut directors, not necessarily first time producers, but it’s their first time directors. And there is an absolutely independent spirit amongst the films, and everyone has felt the same stress. Everybody has jumped over very similar hurdles and you hear very similar stories.

Tia Spanos Tsonis: And so sharing those stories together, but also sharing them with the world. And to have an interview with you, it’s just amazing. Who would’ve thought a year ago that I would be talking to you about our film? It’s very humbling and it’s extremely beautiful and important for us to share these stories. And thank you so much.

Antonis Tsonis: We’re very grateful, yes, for your time.

Brando with a Glass Eye is playing at the Slamdance International Film Festival.

You can learn more about the film by visiting their website.

What did you think about the interview? Did anything surprise you? Share your thoughts with us on X @MoviesWeTexted or leave a comment below.

You might also like…