“In the entertainment business, you’re not supposed to let your practice sh-t out. It ruins the mystique.” is how Llewyn Davis expresses his carelessness for a box of childhood remnants his sister intends to hand back to him. Inside Llewyn Davis, the Coen Brothers most recent masterpiece inspired by the life of Folk musician and guru, Dave Van Ronk, is a great example of a movie putting an entire genre of music on the map for a generation of moviegoers. I know it certainly played a vital role in reconstructing my tastes in music and art alike. The quote above holds major significance in connecting Llewyn Davis to the recently released biopic on the mystifying, enigmatic figure of Folk icon, Bob Dylan, in A Complete Unknown.

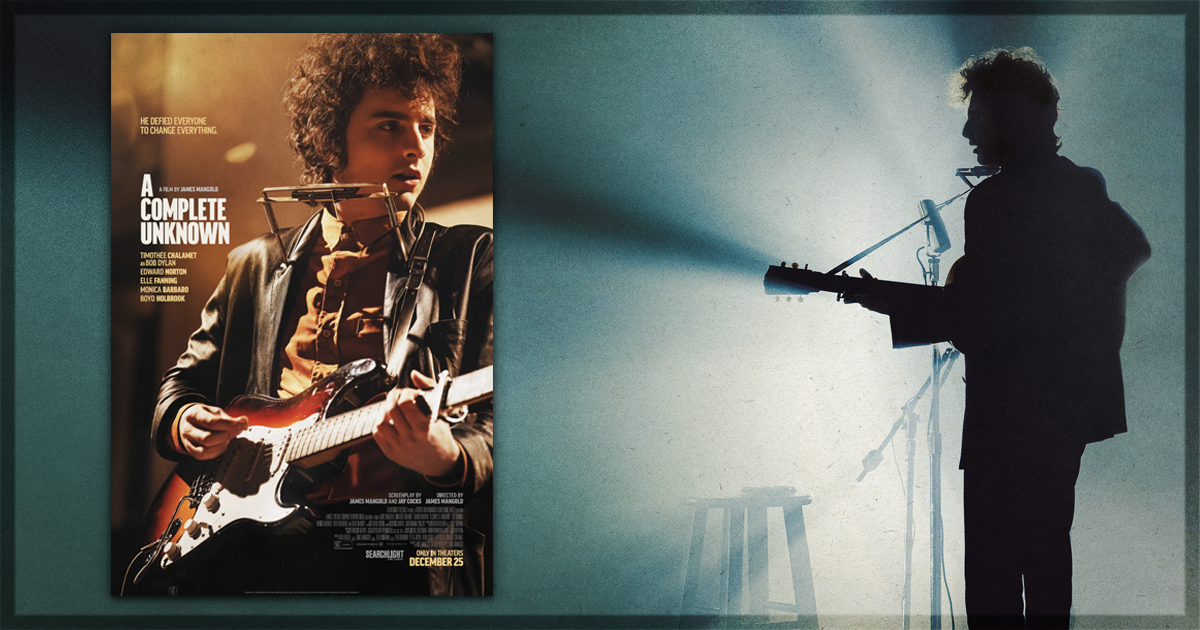

James Mangold, the longtime Hollywood journeyman drawn to the stories and figures that shaped the music industry in the mid-20th century returns to the 1960s with Timothée Chalamet as Bob Dylan. Chalamet, who has enjoyed quite a diverse set of roles across a variety of genres since he burst into stardom turns in a mighty fine performance as Dylan. Although it initially seems like he was miscast, we should have turned to Paul King’s Wonka to understand Chalamet’s physical and vocal range. With a voice as distinct as Dylan’s, any impressionist could pretend to be Bob for a few moments, but Chalamet embodies him with remarkable precision. From the occasional outbursts of snark, the low-hanging eyes peering just above his harmonica’s harness or behind the puff of a cigarette, Chalamet rises above cheap cosplay or considerations as an overpaid impressionist. The cadences are so evocative of Dylan’s voice you may convince yourself they ADR’d (Automated Dialogue Replacement) Dylan’s old recordings over Timothée as he opens his mouth to sing.

This impressive recreation of the Folk scene from 1961-1965 extends to the rest of the cast as well. Featuring Edward Norton as Pete Seeger, Monica Barbaro as Joan Baez, Elle Fanning as Sylvie Russo, and a scene-stealing Boyd Holbrook as Johnny Cash, A Complete Unknown is a star-studded showcase if not anything else. And really, there isn’t much else to say about it other than that. Despite the likeness the actors evoke against the warm fuzz of retrograde film grain, A Complete Unknown has all the merit and weight of a high-budget TV special that riffs on the important notes in Dylan’s journey from the unknown into a historic legend.

Biopics on the music industry’s icons are guaranteed cash cows for whichever studio holds the rights (or is willing to pay enough for the songs). However, most of them have been in an artistic freefall for decades, and as redundant as it sounds, A Complete Unknown continues that trend. Dylan, who is recognized as a contrarian on multiple occasions throughout the film is pigeonholed by a script that appears to generalize his stardom. What should be an obstructive and defiant account of commodifying music that rallied people around social justice and environmental awareness, A Complete Unknown is instead more like “Bob’s Best Hits” rather than an attempt to understand how Dylan’s persona reshaped a genre in relation to sudden political developments. As all art is inherently political, Mangold and writer Jay Cocks absolutely neutralize any sort of political stimulus within the framework of the film.

Sure, you may get nuggets of “The Red Scare” or political marches that were taking place from ‘61-’65, but it doesn’t inform the film in any capacity. We already know the political tension at the time motivated Dylan’s music, but how that bears on the film in an emotional capacity is all but worthless. Not only does Bob face the chants and concerns of political assassinations and nuclear paranoia, but the film also chooses to account for his already well-documented relationship with Joan and Sylvie. Some semblance of honoring the truth is a necessity in biopics, but there are no artistic statements about these complicated moments in his life. There is no sense of escalating conflict or palpable textures internalized in Bob’s rise as a voice of the moment and the future. What’s even worse is that the film appears to evade any sort of overarching dilemma that ebbs and flows with the processes of all narratives to reach a resounding climax. We already know Bob Dylan goes electric, but what does Mangold have to contribute to that development? Virtually nothing.

The most recent biopic that comes to mind when we’re talking about great examples of the subgenre is Rocketman. The Dexter Fletcher-directed piece starring Taron Egerton as Elton John is a beautifully eccentric and wonderfully expressive interpretation of Elton’s musical career. In comparison to A Complete Unknown, Mangold appears to have no sense of interpreting events as an opportunity to express something meaningful. An even better example of this notion is Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There. A film where six different actors portray six separate personas of Bob Dylan throughout different stages of his life to evoke how Dylan reinvented sound by continuously reinventing himself. In a cast that includes Christian Bale, Heath Ledger, and even Cate Blanchett, Haynes adequately explores Dylan through the acting style each actor contributes to best express how Bob Dylan has marks of recognition without diminishing the vastness of his personality.

Including documentaries such as Don’t Look Back, No Direction Home, and even his brief appearance in The Last Waltz, no matter how often Dylan has been documented, there is no way to accurately define how he’s been crystallized throughout history as a personality-shifting icon. For Mangold to completely abolish any subjectivity, or mystique orbiting around Dylan’s planet-sized persona is precisely the type of “practice shit” that shouldn’t be let out. It’s amateurish, naive, and a deeply impersonal attempt at honoring one of the greatest artists of our lifetime by reducing his sound, image, and relationships to the most rote and pedestrian beat-for-beat recreation of his path toward history’s Hall of Fame.

This probably could have been gathered by the trailers and synopsis, but to see it unfold before you, as repetitive as it is, is completely shameless in its attempts to siphon more money out of the audience. When Dylan glances at his first major check (a whopping $10,000) it is the only instance in the film where dollar signs seem to impress, or maybe even motivate him. The film doesn’t want to fool you into thinking Dylan wasn’t about the money, but the way in which this segment of his life unfolds is directly about retracing the songs we already love, in a part of his life we’re already aware of to make absolutely sure we continue to stream, purchase, buy, trade, sell any music that has been commercialized by this film. Why do you think Awards predictors anticipate a big appearance for this film throughout the circuit? Not because it’s saying anything meaningful about Bob Dylan reinventing music, but because it is a box office smash hit. This entire project has nothing to do with opening the doors to understanding the stanzas of Bob’s lyrical poetry through the questions we have about him in relation to the time period. And again, commercial movies are about making money, but when it comes to honoring the image of someone who pushed their lips against a harmonica as he stressed guitar strings without having to contextualize his path to that point is the selfless and compassionate traits meaningful art is founded upon. There is no such compassion or selflessness in this film.

Regardless of how popular Dylan’s music was, is, and will continue to be, James Mangold and Jay Cocks have no business reducing a story about Bob Dylan to something this artless to try and worm their way onto gold embroidered stages. Outside of the performances that make the film worth watching for the most of the runtime, there is nothing in here worth reconsidering about Bob, Joan, the 1960s, Folk music, or the passing of the torch from Woody to Johnny to Bob. There are already so many well-documented pieces on the emergence of the Folk scene you couldn’t justify a comprehensive reason for this movie’s existence outside of awards and playlist replays on your favorite app. Which registers A Complete Unknown as an even larger categorical failure.

Fifty years after Dylan reshaped the enterprise of music by tapping into the wandering souls across America’s plains, valleys, metropolitan skylines, and belts, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The award is cited, “For having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”, and the film even includes it in the postscript to end the film. What makes this final gesture even worse is that they note that Dylan never showed up for the award despite being only the twelfth Nobel laureate from the United States. Perhaps a statement, an action, a movement on Bob Dylan’s part that expresses his writing, music, and art was never about the awards. Unfortunately for Fox Searchlight and James Mangold, it’s only about taking the stage from Bob to uplift themselves.

A Complete Unknown is now in theaters.

Learn more about the film, including how to buy tickets, at the official website.

You might also like…

‘LOST ANGEL: The Genius of Judee Sill’ Interview with Filmmakers Andy Brown & Brian Lindstrom

‘Better Man’ Review: Robbie Williams Biopic Lacks Charm