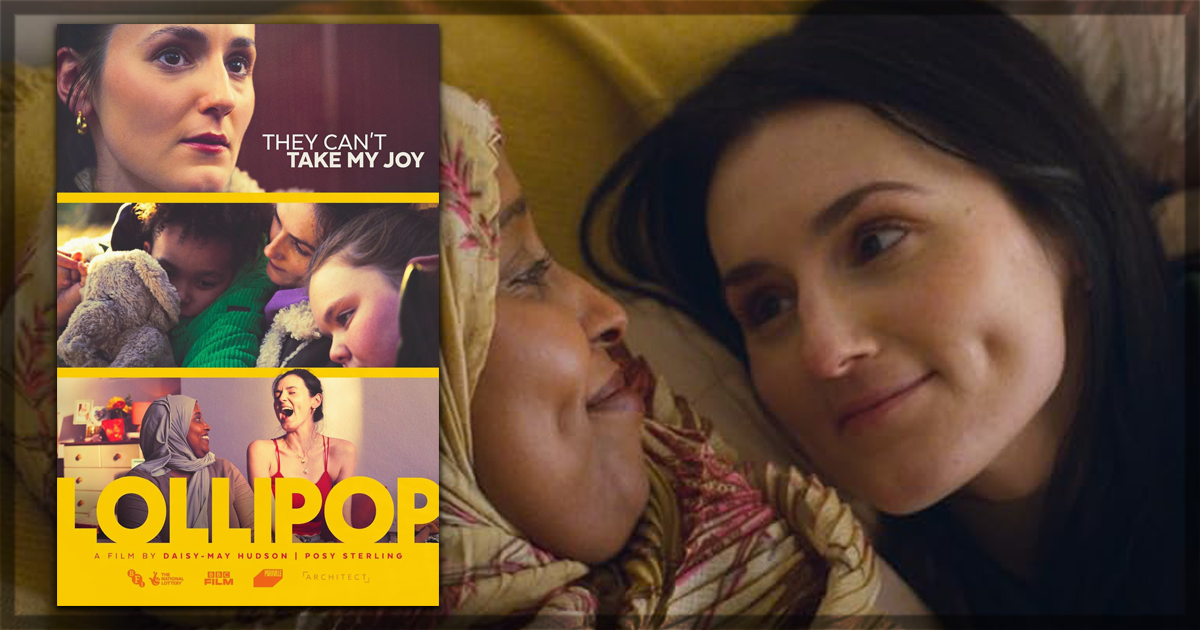

The title of writer-director Daisy-May Hudson’s latest feature, Lollipop, hearkens to a sticky-sweet childhood candy and its colorful, innocent connotations. Yet this film opens with a collect phone call playing over the BFI funding title card, notifying the recipient that it is from a British prison and how to decline the call if desired. Here, we hear Molly (Posy Sterling) tell her two children it is only a few more sleepovers until she gets to take them home for good. Molly is a young mother who has just been released from a stint in prison following an acrimonious split with an ex. She is buoyant upon release, charging her phone at a corner shop and calling the care home that is looking after her children.

But the difficult truth hits hard; custody of her children will not be automatically granted upon her release, as she has no house, no funds, and no employment. She has to start almost entirely fresh, but with raised stakes with the burden of her past threatening a stable life and future with the children she adores. Her mother Sylvie (TerriAnn Cousins), who gave Molly the nickname “Lollipop” for her sunny disposition as a child, offers little tangible support; the family history is not covered in detail in Hudson’s naturalistic, elegantly witty script, but she lays the foundation for Molly’s own struggles in this emotional distance.

A chance encounter with Molly’s childhood friend Amina (Idil Ahmed), who has her own struggles with a crooked landlord and single motherhood, promises a new anchor for both their futures. Amina is the only person who can talk Molly down from panics and emotional explosions, and perhaps together, they can take their future into their own hands and refuse to bow to the injustice of their situations.

Molly is a difficult character to love at times. Hudson and Sterling paint her as neither any sort of villain nor the perfect victim, as she fiercely loves her children and seems trapped by circumstance but often turns on a dime to full-blown emotional outbursts and impulsive decisions – ones that, in the presence of caseworkers and potential employers, can very easily derail her precarious burgeoning stability. What emerges is a fully-rounded, flesh-and-blood portrayal of a complicated person who has agency in her situation and life choices but, to stretch a poker metaphor, the house still holds the power no matter how strong or weak her hand. Ahmed’s performance is equally magnetic, with Amina’s ability to better regulate her emotions and calm Molly, who is hiding a stewing resentment of her own situation.

Hudson has often focused her work on the often ignored but all-too-common realities of poverty and economic instability in the UK. As in many Western nations, social mobility and pulling one’s self up by the bootstraps are common myths (indeed, the latter’s phase started as satire for an impossible task). These issues and situations are not unique to the UK, but after over a decade of Conservative government hostility to social welfare programmes, council budget cuts making housing and support less and less available, and increasing wealth disparity, these situations are far more prevalent than many film depictions of the country suggest.

A catch-22 facing many whose lives have gone off the rails, for prison or other reasons, is that it is often impossible to get a flat without a job, a job without a flat, and a bank account without either. This makes employment, housing, and financial precarity almost impossible to break out of without good fortune or external support. Lastly, there are only 12 women’s prisons in England and Wales out of 117 total, meaning that women are often transported many miles from their homes and families, and their children are taken into care as a result.

Here, Lollipop portrays a modern tragedy without sentimentality. Molly’s maddening journey does not need embellishment, and the truth of life after prison is not over-explained for the viewers. Instead, her single-minded quest unfolds with no judgment for the paths she pursues and the many obstacles in her way.

While the material covered is undoubtedly heavy, Lollipop is not without levity. A late scene where Molly and Amina confront the latter’s dishonest landlord archly balances absurdity with genuine threat and exposes the hypocrisy of trying to solve injustice through civility. This friendship, as well as Molly’s relationship with her children, comes through in laughter, hugs, and jokes as much as in deep confessions.

Production company Parkville Pictures, known for producing Desiree Akhavan’s films Appropriate Behaviour and The Miseducation of Cameron Post, more recently produced Nida Manzoor’s Polite Society last year. Their mission statement is to find films that are “meaningful, provoking, and inspiring,” and Lollipop feels a strong fit among these stories of women on the margins of society in very different senses. Heartbreaking and heartwarming in turn, while never giving into emotional manipulation, Lollipop celebrates women’s resilience, ingenuity, and strength in the face of systemic oppression. Without glamorizing life on the edge or simplifying the struggle of class solidarity, the film’s power comes from a superb script and a slate of fully embodied performances.

Lollipop recently screened at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

Learn more about the film at the Edinburgh site for the title.