There is a long history of verite cinema within the documentary format. Within conversations that surround the ethics of this more observational form, we discern a conflict: on the necessity of intervention. This is a contentious topic, particularly within the filming of nature documentaries, where the observer must not intervene so as to get an unaffected slice of the article they are documenting. Inma De Reyes, director of The Boy and the Suit of Lights, places herself within the life of a young aspirational matador and observes both the passing of time and baton of tradition, while taking steps not to intervene with the choices made.

In The Boy and the Suit of Lights, De Reyes chronicles Borja Miranda, a young, underprivileged boy from Spanish village Castellon. The film takes place over the course of five years, with De Reyes standing back from the drama, solely observing Borja as he learns the matador profession. The village of Castellon has a long history of bullfighting – and is colloquially known as Spain’s bullfighting capital – but for De Reyes, who originates from the village, this was a shock to her as she had never witnessed a bull fight. The idea of bullfighting being ingrained into the fabrics of Borja’s masculinity is tinged by the tradition of it all. Borja wants to follow in the generational footsteps of his grandfather. To Borja, there’s a romanticism to it, but is this just the impressionable disposition of a child’s respect for his grandfather? This is where De Reyes portrays the act of bullfighting as an internal conflict for Borja, who wants to lift his family out of poverty. The film presents the act of bull fighting as a wealthy endeavour within the Castellon community, one that will help Borja and his family. This is without De Reyes glorifying it; she is instead acutely aware that it may be the only option for Borja to achieve the task of salvation thrust upon his shoulders.

A mainstay in contemporary verite documentary filmmaking is the hybridisation of verite and indirect cinema, where subjects are documented in real scenarios but also conduct interviews. The Boy and the Suit of Lights solely follows Borja, doing so with a more refined approach that is almost too intimate. In her director’s statement, De Reyes states, “I could see in young Borja’s expressive eyes that he felt a sense of pressure from his family that did not match well with his personality.” We get close-ups of Borja as he learns to wield the ‘muleta’ and various other articles that are linked with the profession, but we are removed from his thoughts in a way that this conflict is barely implied and far too often inferred. Borja’s interactions with younger brother Erik, friends and mother Raquel are the few moments where Borja opens up, but even then he is a too reserved participant in this documentary, not able to provide much more

The optics of bullfighting are tenuous at best. De Reyes includes an anti-bullfighting protest that occurs while she is filming, and PETA calls the sport barbaric: a “ritualistic slaughter of a helpless animal.” A strength of the film is that De Reyes, through her observations, doesn’t indict Borja for his decision to become a matador, nor does she ratify it. It is a film that refuses to be dogmatic on the idea of bullfighting, choosing to portray the concepts of familial expectations and financial parity much more intimately while implying a real sense of urgent empathy for Borja.

There is another element to the ethical conundrum within the direct cinema stylings of The Boy and the Suit of Lights: the physical appearance of De Reyes and her camera. If De Reyes does not continue following Borja for the five years she does, does he still continue his path? The film wants you to believe that her presence, as removed from the situation as she appears to be, does not provide an influence. This does not appear to be a fault of De Reyes’ but of the pseudo-reality that is imposed on Borja by the presence of the lens of the camera itself.

The production miracle that is 2014’s Boyhood – for those unfamiliar, the fictional story was filmed across 12 years, while the cast literally grew up in front of your eyes – was a form of docu-fiction, in that it imposed the contemporary ‘real’ onto the fictional form. For Linklater, his coming-of-age story was fiction. For De Reyes, who filmed a form of reality over five years, a similar environment to Boyhood is imposed. Borja matures into puberty on screen, and with it we get a reality that contradicts the essence of Boyhood: insight into the specific goings-on of Castellon life. De Reyes’ film seems to levitate, her camera a fluid lens latched onto the singular entity of a rookie bull-fighter but also one that can be transposed further onto a society attached to tradition.

The Boy and the Suit of Lights (El niño y el traje de luces) premiered at the Sheffield DocFest.

You might also like…

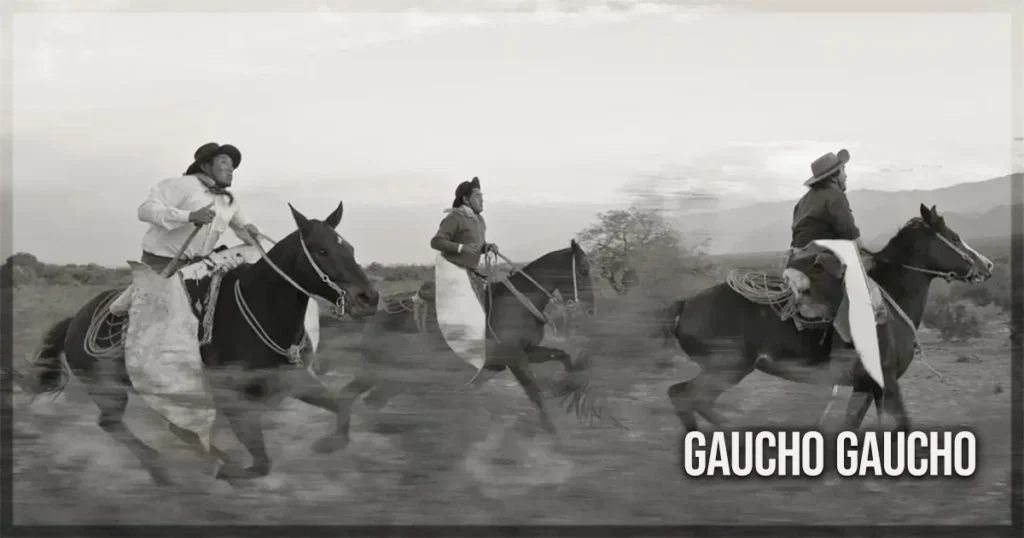

‘Gaucho Gaucho’ Review: An Intensely Immersive Documentary